Care Workers’ Experiences of Emergencies with Korean Older Adults: A Qualitative Descriptive Study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated the nature of nursing care workers’ experiences of responding to emergencies involving Korean older adults to prepare measures to strengthen nursing care workers’ practical abilities in this regard.

Methods

This qualitative descriptive study used focus-group interviews and qualitative content analysis. Two focus-group interviews with 16 care workers from 16 nursing homes and home-care centers were conducted between February 1 and April 28, 2019. We collected data through these two focus-group interviews.

Results

Of the 16 participants, 11 were care workers from nursing homes for older adults and five were from home-care centers. Altogether, we formulated 180 meanings from the original data and derived 64 codes from these meanings. Five categories were identified through systematic conceptualization: “panic about emergencies”, “difficulty recognizing an emergency”, “desperate need for real education”, “unsystematic emergency responses”, and “dealing with the aftermath of a patient’s death”; the categories were extracted from 21 subcategories.

Conclusion

Care workers faced sudden emergencies while caring for older adults and coped with them based on their previous experiences. Nevertheless, they faced difficulties in recognizing emergencies. Our findings may help institutionalize systematic and consistent on-the-job training programs to augment care workers’ emergency preparedness.

INTRODUCTION

In 2020, older adults (aged 65 years or older) constituted 9.3% of the global population, with this figure estimated to reach 16.7% by 2050[1]. To respond to the needs of the aging population, the Korean government operationalized the Long-Term Care Insurance System in 2008 [2], which facilitates older adults’ independence and reduces the burden on their families. When they become incapable of living independently, due to deterioration resulting from geriatric diseases.

Care workers are professionals and core manpower who provide long-term care services, including physical and housekeeping support, usually for older adults. Care workers accounted for 89.5% of the total workforce employed at long-term care institutions in 2020 whereas nurses, nurse’s aides, and social workers accounted for 0.7%, 2.6%, and 6.0%, respectively [3]. Along with cognitive impairments, older adults cared for by care workers often suffer from a combination of infections and diseases, such as those of the respiratory, digestive, cardiovascular, and central nervous systems [4]. With the frailty rate ranging from 19% to 75.6%, the frequency of emergencies in long-term care institutions can be up to four times greater than the rate among community-dwelling older adults [5]. Additionally, the number of long-term care recipients brought to the emergency room because of atypical and ambiguous symptoms has been increasing [6]. They are also likely to have long-term illnesses and recurrences, high medical expenditures, and high mortality rates [7].

Research has emphasized the importance of care workers’ ability to detect an emergent situation by recognizing abnormal changes in older adults they care for and quickly and correctly responding to the emergency [8]. Some nursing homes do not have nurses or nursing assistants, and even if they are available, they tend to work until 6 p.m. Thus, the responsibility often falls on care workers [9]. Also, home care workers are often the sole care providers of older adults in the absence of their legal guardians. Consequently, care workers are usually among the first to notice changes in most emergencies while caring for older adults [10].

In a recent quantitative study in Korea, 90.5% of nursing home care workers and 70.4% of home care workers reported experiencing emergency situations among their older adult patients, which indicates that care workers frequently face emergency situations at work [11]. An emergency situation is directly related to the life of an older adult, and care workers often experience challenges regarding how to deal with the emergency situation, causing them to panic because they feel they lack the necessary knowledge and skills [12]. Care workers, who are non-medical practitioners and mostly women with a high mean age, strive to cope comprehensively with emergencies. Care workers reported they lack the ability to cope with emergency situations, with 60.57 points in the facility group and 57.53 points in the home group (out of 100 points) [11]. The emergency practice education currently provided to care workers is a 10-hour program comprising four hours of theoretical and six hours of practical education. After being certified and commencing their professional responsibilities, care workers receive only three hours of education on how to cope with an emergency: two hours of theoretical and one hour of practical education as part of a program on dementia [11]. Thus, care workers not only consider emergency education as the most difficult unit of study to understand in their training course, but also evaluate their ability to perform first-aid tasks as poor [13]. Care workers are not provided an opportunity to receive continuous training or legally mandated job training; thus, it is difficult to have up-to-date knowledge and skills required for dealing with emergencies. Most institutions run their own emergency education courses, but it is difficult to guarantee the quality of such self-education. Further, some small institutions find it difficult to conduct such courses themselves, which also limits the quality of education in various respects [14].

The experiences of care workers who face emergencies must be understood prior to developing educational programs to identify challenges and necessary resources. A proper education will be helpful for them to appropriately deal with the emergency situation to prevent injuries from accidents, reduce complications or disabilities, and promote recovery among older adults [15]. Care workers’ emergency response skills are directly correlated with the survival of older adults and the prevention of serious complications [16]. However, research on this topic is still lacking. Few quantitative studies [11,17] have investigated the experiences and individual behaviors of care workers in real emergencies. To our knowledge, no qualitative study has investigated the perceptions and aptitude of care workers responding to emergencies.

This study aimed to present an in-depth exploration of care workers’ experiences regarding physiological emergencies among older adults in Korea to improve nursing care for this population. Specifically, this study intended to answer the following question: “What are the experiences of care workers coping with emergencies that arise during the care of older adults?”

METHODS

1. Research Design and Procedure

This study employed qualitative content analysis to explore care workers’ experiences of coping with emergencies involving older adults.

2. Participants

We recruited 16 care workers from nursing homes and home care centers through snowball sampling. According to the results of a previous study [18], it is important for research participants to have enough experience in relation to the research question. Therefore, the following specific selection criteria were used in this study: (1) worked as a care worker for more than a year, (2) experienced an emergency, (3) have adequate communication abilities, and (4) understand this study’s purpose and have a willingness to participate in the study. To ensure the diverse pool of participants, sampling was conducted at 11 nursing homes and five home care centers.

3. Data Collection

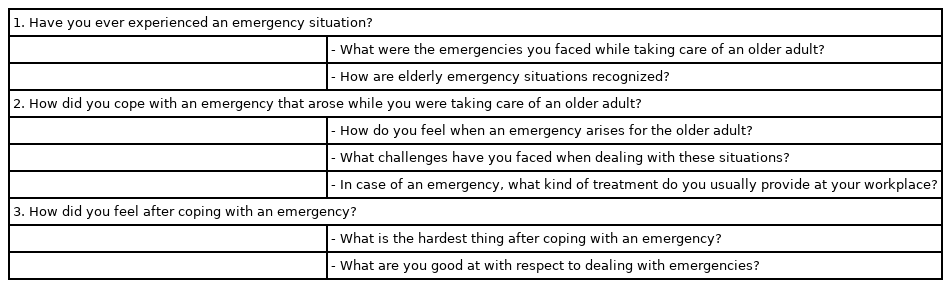

To facilitate open discussion, we ensured that all participants are unrelated, and the focus group did not include the care workers’ supervisors. The 16 participants were divided into two groups: the first comprised eight participants from four nursing homes and four home care centers, while the second comprised eight participants from seven nursing homes and one home care center. One researcher moderated focus group interviews, and another researcher was present as a note taker to record the participants’ behaviors and facial expressions. During the interviews conducted in Korean, participants were asked about their perception of emergency situations, how they responded to the emergencies, and the difficulties they faced while dealing with emergencies. We collected data from February 1 to April 28, 2019. Two interviews were conducted per group and each interview took approximately 2.5 hours. We designed a semi-structured interview guide for the in-depth interviews (Table 1). All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were compared with the original audio recordings to confirm accuracy, and random identifiers were assigned to the participants. All qualitative data, including those collected via interviews and field notes, were managed using NVivo 10 software (QSR international, Melbourne, Australia).

4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Graneheim and Lundman’s method [19] of content analysis. Two researchers carefully and independently reviewed the transcripts to familiarize themselves with the data and recorded their initial findings regarding meanings and patterns related to the care workers’ experiences around physiological emergencies. Each interview was considered one unit of analysis. Afterwards, the text was divided into meaning units, comprising words, sentences, or paragraphs containing aspects related to each other through their content and context. The meaning units were then condensed, while still preserving the core. Each condensed meaning unit was labeled with a code, and subcategories and categories were created. Although the analysis process was systematic, we had to move back-and-forth between the whole and parts of the text.

5. Ethical Considerations

The institutional review board of the researchers’ affiliated university approved this study (approval number: SHIRB-201908-HR-096-01). We informed potential participants that their identities would remain confidential and that the data would be used only for research purposes and destroyed immediately after study conclusion. Participants were also informed of their right to refuse participation or withdraw participation at any time without any repercussions. We selected individuals who voluntarily signed the consent form after reading the information sheet, and we offered them a small compensation for participating.

6. Trustworthiness

To ensure rigor, we followed Lincoln and Guba’s [20] principles of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. We attempted to strengthen the credibility of our analyses through e-mail confirmations and direct interviews with some participants. Furthermore, we examined the context, personal prejudice, judgment, content, and analytical process results to maintain neutrality. These measures aimed to increase consistency. In addition, to secure transferability, a comprehensive description was implemented with detailed explanations of the environmental context, cultural background of the interview contents, and the study participants’ circumstances. Two nursing professors with experience in qualitative research methods and numerous related research achievements repeatedly received advice and reviews to secure research dependability. The confirmability of the findings was enhanced by including multiple investigators for independent coding and categorization of the data, maintaining an audit trail, and comparing interview transcripts with the original audio recordings to ensure accuracy. A professional translation company, Editage, was commissioned for the first translation of this study. Two bilingual researchers reviewed the text. We established the reliability and validity of the properties identified during these steps by consulting two researchers in gerontology and emergency nursing who have expertise in qualitative research.

RESULTS

1. Sample Characteristics

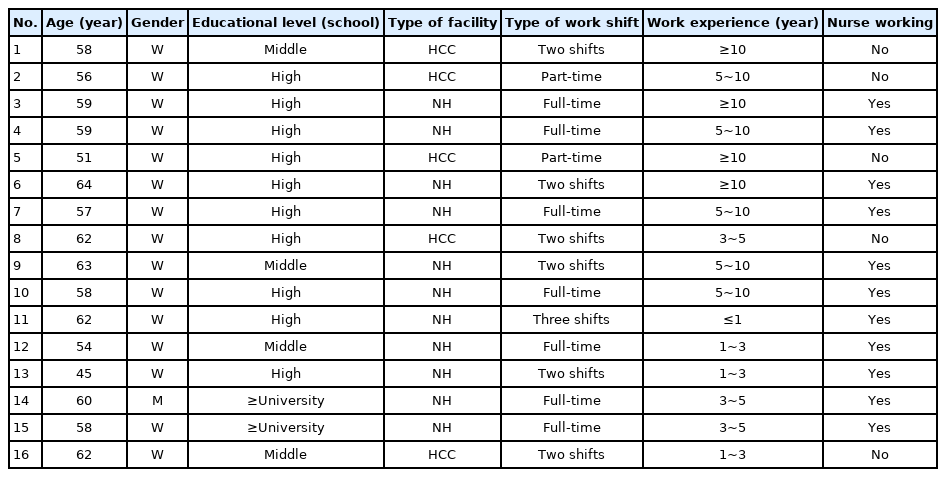

Of the 16 participants, 15 were females (93.8%). The mean age was 58 years old. Most participants had 5-10 years of care experience (31.3%), and four participants (25.0%) had more than 10 years of care experience. Most participants (62.5%) were high school graduates. The study participants worked in nursing homes and nursing care centers (Table 2).

2. Care Workers' Emergency Response Experiences

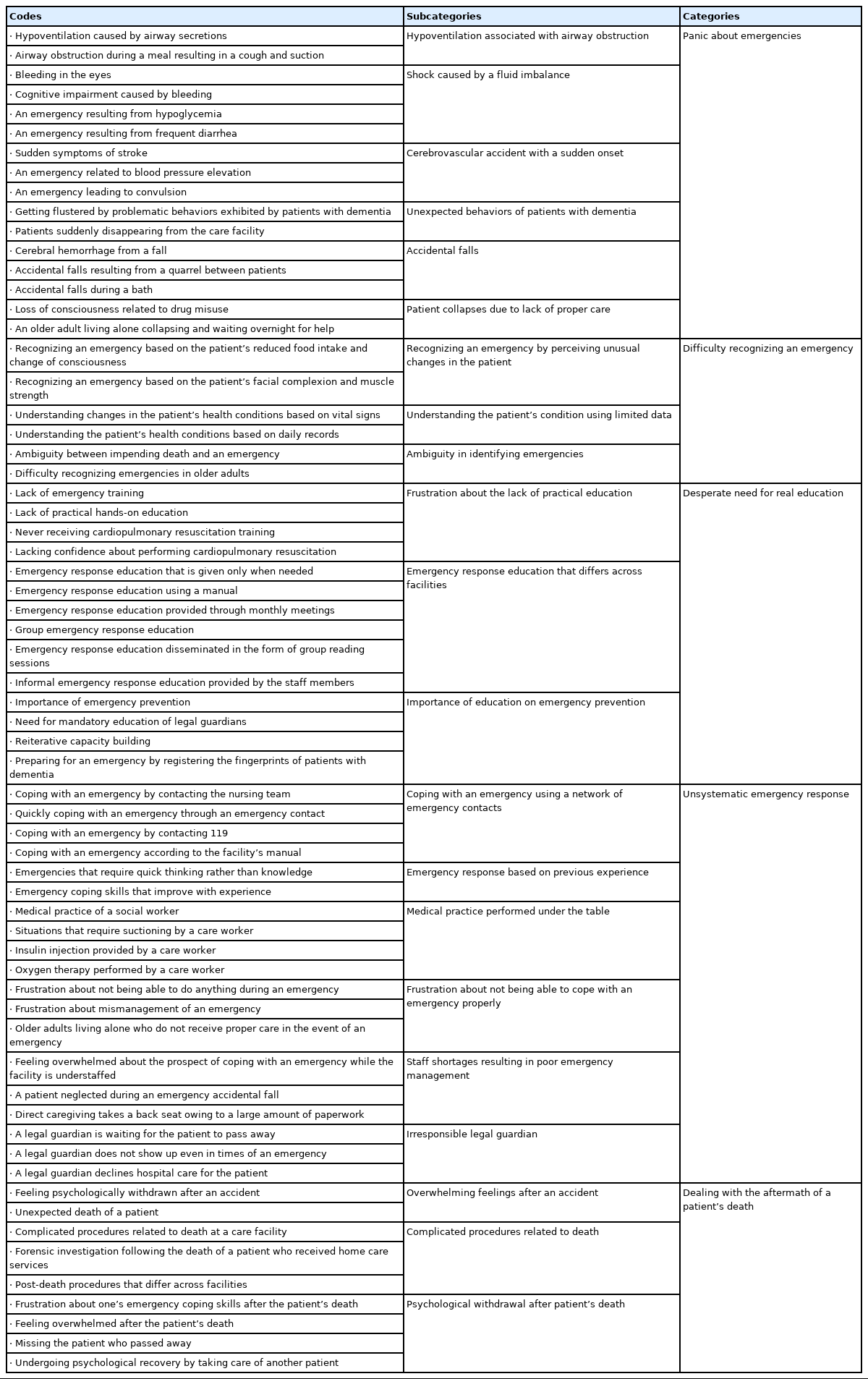

We derived 180 meanings from the original text. Furthermore, we extracted 64 codes from these meanings and grouped them into 21 subcategories. We extracted five categories from these subcategories through systematic conceptualization: “panic about emergencies”, “difficulty recognizing an emergency”, “desperate need for real education”, “unsystematic emergency response”, and “dealing with the aftermath of a patient’s death”(Table 3).

Meanings Derived from the Care Workers’ Descriptions of their Emergency Response Experiences Concerning Older Adults

Category 1. Panic about emergencies

Participants reported they had faced various unexpected situations while working at care facilities, such as dyspnea due to airway obstruction, accidental falls, cardiovascular disease, and unexpected behaviors of patients with dementia. Participants felt shock and panic in the process of coping with these unexpected emergencies alone.

My patient had his airway obstructed by phlegm. It aggravated his respiratory condition. (Participant 8)

I was feeding an older person, and suddenly she was aspirated and coughed. She suddenly stopped breathing and head dropped, so I was so embarrassed. I just patted and stroked her back, and it took about a minute or two, or about a minute, and it came back to life like this. At that time, I was really shocked. (Participant 2)

Participants also reported seeing their patients undergoing sudden shock due to hypoglycemia or diarrhea.

My patient had diarrhea in the morning. It was so severe that his pants and bedsheet were soaked in his feces and had to be thrown away. He kept telling me something was off, and his eyes rolled back, and he fainted suddenly. This occurrence was an emergency that I experienced. (Participant 6)

Additionally, participants experienced emergencies wherein their patients had a stroke accompanied by muscle weakness, blood pressure over 200 mmHg, and convulsions. Participants were heartbroken and panic by the patient's sudden change of condition, which was a serious threat to life.

He didn’t drink any water that day, even when it was about time for him to get up. I asked him to squeeze my hand. He could not squeeze at all with one hand, and the other had barely any strength. I realized that the patient was in a serious condition and contacted 119 to take him to the hospital. The doctors told us that the patient had experienced a stroke. (Participant 7)

Category 2. Difficulty recognizing an emergency

Participants claimed that it was difficult to judge whether a patient was experiencing an emergency or was about to die, as older adults constantly complained of feeling sick. They also felt frustrated about the lack of methods for detecting changes in health conditions aside from vital sign measurement or keeping daily logs.

Participants shared how they recognized an emergency, including perceiving unusual changes in the patients’ status, such as shortness of breath, cognitive impairment, or changes in the skin tone or temperature.

Sometimes they exhibit cyanosis and breathe heavily. Heavy breathing, fast pulse, and cognitive impairment are the first symptoms I notice. Once these symptoms are observed, I measure vital signs. Sometimes, these symptoms lead to an emergency, but they can also resolve on their own. (Participant 3)

Participants found it difficult to identify life-threatening emergencies while caring for older adults because the patients constantly complained about being sick and care workers could not distinguish between serious conditions and general concerns.

I hear ‘I feel dizzy and nauseous’, ‘My chest hurts’, ‘My this and that hurts’ from my older patients all the time. It is difficult to know when they are actually having an emergency since they always complain that they are in pain. (Participant 7)

Category 3. Desperate need for real education

Participants received emergency response education through an emergency response manual provided at their care facilities, monthly meetings, or group training sessions. However, they realized the need for strengthening formal education because they had to rely on informal education from their peers for some procedures needed in emergency situations such as tracheal suction or application of oxygen. Participants who were informally educated on emergency management by their coworkers based on groundless information expressed confusion about the discrepancies in the emergency coping strategies taught in different facilities.

He would ask a coworker a question and then ask another coworker the same question and tell him his answer was wrong if it differed from the previous answer. That is why we need professionals to educate us, not us educating each other. (Participant 5)

Furthermore, care workers experienced a greater need for practical education rather than theory-focused education. They expressed frustration about not receiving practical education.

Care workers need repetitive and practical education tailored to on-the-job needs. (Participant 16)

Category 4. Unsystematic emergency response

Participants reported using different principles approach where they relied on previous experiences to cope with an emergency instead of applying the knowledge they had learned. To cope with a situation promptly, they often resorted to methods that defied principles of effective management. They reported different methods for different emergencies and stated that emergencies were often not systematically managed.

There are situations where I have to do things based on my experience instead of following the principles I was taught. I know what I am doing is against what I was taught, but sometimes I just have to act and think quickly when there is an emergency. (Participant 7)

Participants had sometimes responded frantically to emergencies while caring for older people. They expressed regret about not responding appropriately due to inexperience and using groundless methods.

When facing an emergency, I was so busy responding to that situation as quickly as possible and could not think about anything else. But, looking back now, I find areas where I was inexperienced. I should have followed the basic principles more closely to do a better job. (Participant 8)

Category 5. Dealing with the aftermath of a patient’s death

Participants reported feeling depressed upon witnessing their patients’ death and experiencing an unbearable emotional burden when the emergent situations was not handled properly. They felt psychologically withdrawn as they blamed themselves for not providing adequate care to their patients when facing an accident and as they went through a series of complicated procedures including police and forensic investigations after their patients passed away at the long-term care facilities or home.

I tried to open the door to my patient’s room, which was stuck. When I managed to open it, I saw the patient collapsed on the floor. I just stood there and checked whether the patient was breathing, which he was not. He had passed away. My heart sank as I realized that this had been an emergency. I never thought I would face one. (Participant 1)

The patient fell, and the person who has the most shock is the patient himself, but we also feel a lot of withdrawal in our own way. (Participant 1)

Things get complicated when a patient dies at the care facility. Investigators from the National Forensic Service and police officers visit the facility to inquire about the situation. Patients are now taken to the hospital if they are in a serious condition, provided they have legal guardians. This aspect makes the entire process complicated. (Participant 3)

Participants also missed their patients, whom they had grown attached to over time. However, they overcame their psychological withdrawal by caring for new patients.

I took about a month off. I had no confidence to get back to work, so I just stayed home, in a daze, doing nothing. When the center contacted me and told me I could not take any more time off, I was introduced to new patients. (Participant 2)

DISCUSSION

This study examined the emergency experiences of care workers providing care for older adults in long-term care facilities. This study used focus-group interviews. Five categories and 21 subcategories were derived from the participants’ descriptions of their emergency experiences.

We found that care workers faced various emergencies while caring for older adults. They reported feeling overwhelmed when patients suddenly exhibited unexpected behaviors. Participants were anxious about facing an emergency among their patients whose lives could have been endangered even by a small accident. This was particularly true for those with dementia, who are constantly at risk of accidents, and those who use a walker.

In a nursing home setting where work is performed according to organizational structure, care workers’ role in emergency management is not clearly identified [10,21]. However, as the first responders, care workers are required to quickly recognize an emergency, report it to the nursing team, or call the relevant emergency contact number for help. The nurse who receives the report from the care worker is the only medical personnel and takes a leading role in overseeing the emergency, such as deciding whether to transfer the older person to the hospital or not, while providing first aid [21,22]. When there are more than 30 older residents in a nursing home, the standard for staff placement is to have one nurse (or nurse’s aide) and one referral doctor for every 25 older residents. Thus, nurses working in nursing homes make up only 0.7%, which is lower compared with nurse staffing levels in other countries, such as Germany (53.3%), Canada (34.8%), the Netherlands (29.0%), the US (27.9%), and Japan (16.2%) [23]. In the case of home care services, care workers attend alone to provide services so it is hard to receive systematically respond to emergencies. Therefore, to deal with high-quality emergency situations, it is necessary to revise the law regarding the allocation of nurses (or nurse’s aide) and to establish a system for the systematic management of emergency situations.

Participants in this study shared their difficulty recognizing an emergency, because it is not easy to assess what constitutes an emergency, as older adults constantly complain that they are sick every time the care worker sees them. As care workers are non-medical professionals, their medical judgment. Kim and Jung [12] explained that to respond quickly in an emergency, it is necessary to rapidly judge the situation and understand the course of action to be taken. Therefore, care workers need to receive formal education and on-the-job training to learn how to systematically assess abnormal signs and precursors of diseases. This can help them quickly recognize abnormal changes and take immediate actions [24].

The participants reported that they relied heavily on their previous experiences of emergency situations and perceived that there were discrepancies between what they had learned and what needs to be done. In an emergency, they rushed around because they knew they need to take any action to save the patient without sufficient support and help from other healthcare professionals. This made them feel frustrated and overwhelmed because they feel they have no choice other than relying on their experience not on evidence-based practice. Simultaneously, they often regret that they could have handled the situation more properly. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a strategy to prepare them to be a knowledgeable and confident worker who can perform necessary procedures based on evidence.

Participants in this study expressed their disappointment with the lack of opportunities for proper emergency response education and the need for practical education, rather than formal theory-focused education. This is consistent with the results highlighting the lack of practical training for care workers in the study of Lee and Jang [14] and the demand for field-oriented educational content in the study of Kim and Jang [25]. According to a previous study [26], continuous education and training also need to be provided to care workers to improve practical performance and maintain the professionalism of care workers. However, there is no formal continuous or on-the-job training for care workers currently, and the only opportunity to receive emergency care-related is the 3-hour training session for home care workers provided by the National Health Insurance Corporation. In order to equip their workers with proper skills and knowledge, most long-term care facilities have developed their own educational programs, but it is difficult to guarantee the quality of such education. Coordinated efforts are necessary to develop a formal educational program that can be provided by accredited agencies.

O'Neill et al. [27] stated that the first-aid ability of the first responder in an emergency is essential to securing the patient's life and preventing further accidents. Emergency response competency can be developed through repeated practical training, which simulates a real-life situation, along with specialized knowledge suitable for emergency situations [12]. Mobile application-, case-, or simulation-based education, can be utilized as educational methods that reflect these characteristics. In addition, since nurses are needed first and foremost to systematically manage emergency situations for older adults, we propose policy support for expanding the number of nurses by amending the Elderly Welfare Act.

Although long-term care insurance beneficiaries may be more prone to emergencies owing to various circumstances in Korea, even a conceptual definition of emergency situations occurring at long-term care sites has not yet been established and there are no accurate statistical data [21,28]. To effectively deal with emergency situations for older adults that occur in the field of long-term care services, it is necessary to establish a concept through research and discussion, as well as to establish a system for analyzing statistical data and systematically managing it.

This study provides insight into perspectives of care workers working in the long-term care setting with regard to how they respond to emergency situation. This study provides evidence for the need for developing and applying appropriate education programs for care workers. There are a few limitations. We selected care workers from certain regions, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Other limitations include the possibility of research bias, and the fact that the findings are based only on the experiences of care workers. In addition it did not explore the more in-depth emergency response ability of the study subjects by conducting focus group interviews only twice.

CONCLUSION

This qualitative study identified meanings relevant to care providers’ emergency response skills to understand their experiences of coping with emergencies. Participants not only experienced difficulties in recognizing emergencies and abnormal symptoms while caring for older adults but also regretted having to rely on personal experience rather than established protocol, even if they succeeded in identifying the emergency. Therefore, a case-based emergency education program needs to be developed and applied to ensure that care workers adequately recognize and systematically cope with abnormal symptoms exhibited by older adults. However, since this study appraised the experiences of both care workers at nursing homes and home care workers, more multifaceted and repeated research focusing on each of these types of care services is needed. Finally, this study’s findings may establish a foundation for the development of a formal and continuous evidence-based education program aimed at improving care workers’ emergency response skills.

Notes

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Study concept and design acuisition - KSO and BSH; Data collection - KSO and BSH; Analysis and interpretation of the data - KSO and BSH; Drafting and ciritical revision of the manuscript - KSO and BSH.

This study was supported by The National Research Foundation of Korea, grant number (2018R1C1B5084525).

Acknowledgements

None.