The Relationship between Nurse Staffing and Nurse Outcomes in Nursing Homes: An Integrative Review

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this review was to examine the relationship between nurse staffing (number and stability) and nurse outcomes such as turnover rate, retention rate, intent to leave, and job satisfaction for nurses in nursing homes.

Methods

An electronic search was conducted for English articles published between January 2009 and July 2019 using CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO databases. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were included. Nine articles were reviewed and synthesized for the relationship between nurse staffing in nursing homes and nurse outcomes.

Results

In this review, six studies showed that an increased number of nursing staff and stable nurse staffing is associated with positive nurse outcomes, whereas three studies reported no relationship between nurse staffing and nurse outcomes. These inconsistent findings suggest that more research is needed.

Conclusion

Research needs to be conducted to include a more diverse nursing staff and nursing outcome variables. These results can provide evidence of the importance of nurse staffing in nursing homes and lead to a more effective deployment of nursing staff and help for nursing homes’ nurse-staffing policies.

INTRODUCTION

South Korea has seen a rapid increase in the proportion of the older adult population in the world, with about 15.7% of the population in 2018 were elders, and is expected that by 2050, 38.1% will be older adults. To solve the health problems of older adults and lack of family support for older adults, Korea initiated a universal long-term care social insurance system in 2008. With this change, the number of nursing homes (NHs) increased rapidly from 1,332 in 2008 to 3,389 in 2018; during the same period, the number of older adults in NHs increased more than 2.5 times from 66,715 to 163,484, and this increase is expected to continue [1].

Nurse staffing in the NH setting is significant because the long-term care industry is labor-intensive [2]. In NHs, nurses are core staff, affecting the quality of care of residents [A8]. NH nurses provide clinical care, care management, and planning for evidence-based practice, based on timely assessments of residents’ health status [2]. Nurse staffing in NHs is proportionally different from those in acute-care settings. In general, NHs have fewer registered nurses (RNs) and more assistive nursing staff, such as licensed practical nurses (LPNs) and certified nurse aides (CNAs) [3]. For this reason, most research about nurse staffing in NHs includes LPNs, CNAs, and RNs. Suboptimal nurse staffing in NHs has been found to be associated with a lower quality of care and negative health outcomes in nursing staff [3,4].

In the United States, the NH Reform Act of 1987 requires NHs to assign one RN on duty for 8 hours a day, 7 days a week, and a LPN in the evening and night shifts [5]. The guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS, 2001) provided minimum nurse staffing standards to implement the following federal guidelines: RNs: 0.75 hours per resident day (HPRD), LPNs: 0.55 HPRD, and CNAs: 2.8~3.0 HPRD [6]. These nurse-staffing policies aim to improve the quality of care and provide a positive practice environment in NHs through proper placement of nursing staff.

Several nurse staffing-related variables are used in the field of NHs, such as HPRD [2,4,7,8], skill mix (the proportion of professionals) [7,8], and turnover and retention (as a measure of the stability of the workforce) [2,4,7,8]. Researchers have conducted a great number of studies about nurse-staffing levels and resident outcomes in NHs [4,7]. Researchers found that lower nurse-staffing levels relate to lower quality of care. Through systematic reviews, researchers found that increased nurse-staffing levels align with better health outcomes, such as use of fewer antipsychotic drugs, reduced use of physical restraints, lower occurrence of fractures, lower incidence of infection, and lower probability of death in NHs [4,7]. Although more research is needed continuously, the relationship between nurse-staffing levels and resident outcomes has been clearly identified.

Researchers and stakeholders should also consider nursing outcomes when deciding which nursing staff provides health care to residents in NHs. With respect to NH nurse outcomes, lower nurse staffing relates to lower job satisfaction, lower retention rates, and higher turnover [A1,A3-A5,A7,A8]. In contrast, some researchers showed that nurse staffing does not align with nurse outcomes such as tenure, job satisfaction, and burnout [A2,A6,A9]. However, no integrative review emerged that investigated the relationship between the level of nurse staffing and nurse outcomes in the NH setting. Because studies focused on different aspects of nurse staffing and nurse outcomes, findings from these studies need to be reviewed. Through an integrative review of the literature, it is possible to draw conclusions on the relationship between NH nurse staffing and nurse outcomes.

The purpose of this review was to determine the current state of knowledge about the relationship between nurse staffing and nurse outcomes in NHs. Specifically, 1) identify nurse staffing measures and nurse outcome measures used in the literature (2009~2019), 2) summarize the effects of the appropriate level of nursing staff on nursing outcomes, and 3) suggest future research directions to improve nurse outcomes in the NH setting.

METHODS

1. Search Strategy

In July 2019, this researcher conducted a literature search using electronic bibliographic databases such as CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO. The search strategy included terms related to nurse staffing and nurse outcomes. Search terms related to nurse staffing (“Nurse staffing” OR “Nursing staffing”) were combined using the Boolean operator “AND” with search terms referring to the care setting (“Nursing home” OR “Residential facility” OR “Long term care facility” OR “Residential care” OR “Long term care setting”). Also, the search included all references in the included publications for additional articles that were not identified during a bibliographic database search.

2. Inclusion Criteria

Studies published from 2009 to 2019 that met the following inclusion criteria were selected for review. The reasons for restricting the search to literature done since 2009 are as follows. 1) The purpose of this study was to discern recent trends. 2) As the Korean Long-Term Care Insurance Act was enacted in 2008, many changes have been made to the nurse staffing standards of NHs (e.g., easing the criteria for deploying nursing staff, unifying NHs divided according to their purpose, and unifying the criteria for deploying nursing staff). The review was limited to (a) studies focused on nursing staff working in NHs, including RNs, LPNs, and CNAs, (b) studies that examined the relationship between nurse staffing and nurse outcomes, (c) studies published in English, and (d) studies published in peer-reviewed journals.

3. Search Outcome

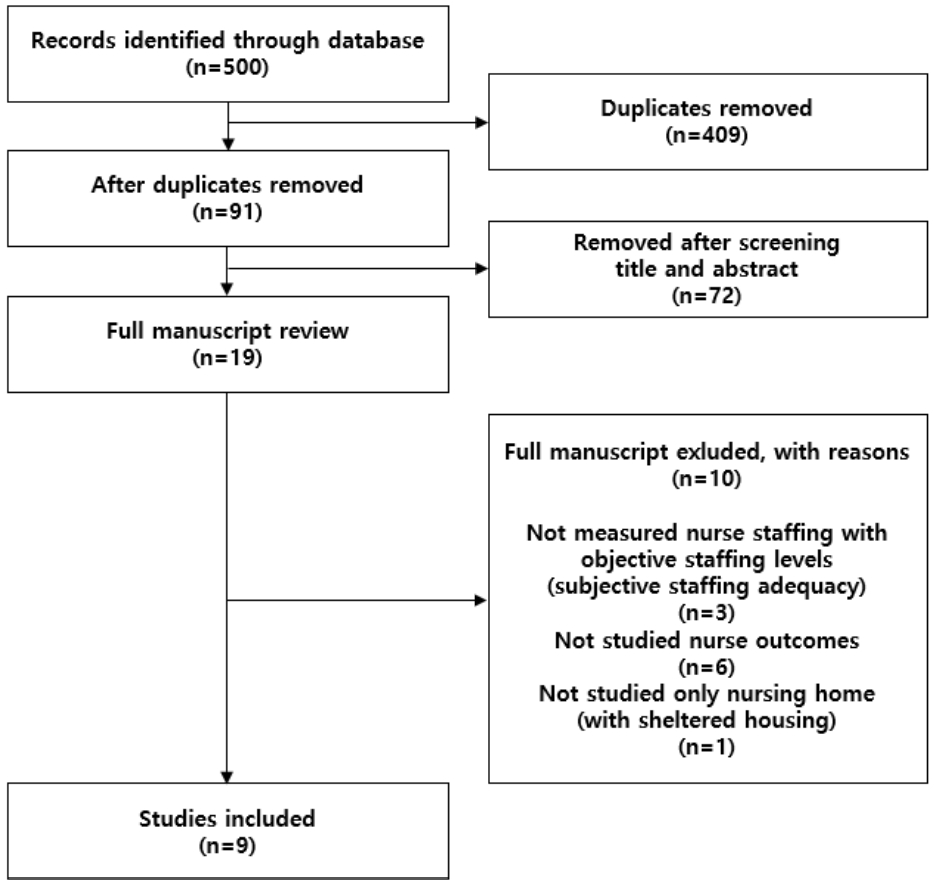

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines directed the systematic review process [9]. In this review, the author identified and screened a total of 500 titles from the search of electronic bibliographic databases. After deleting duplicates, the initial search yielded 91 publications. After screening titles and abstracts, the number of remaining articles were 19. Of the remaining 19 articles, three articles did not use objective indicators in measuring nurse-staffing levels (instead, they used a subjective indicator of the adequacy of nurse-staffing levels), six articles did not measure nurse outcomes, and one article’s setting was NHs and sheltered housing. Through this step, nine articles remained. Therefore, nine articles related to nurse staffing and nurse outcomes were reviewed and synthesized (Figure 1). In this review, a PRISMA diagram explains how sources were identified and selected.

4. Data Extraction/Synthesis and Analysis

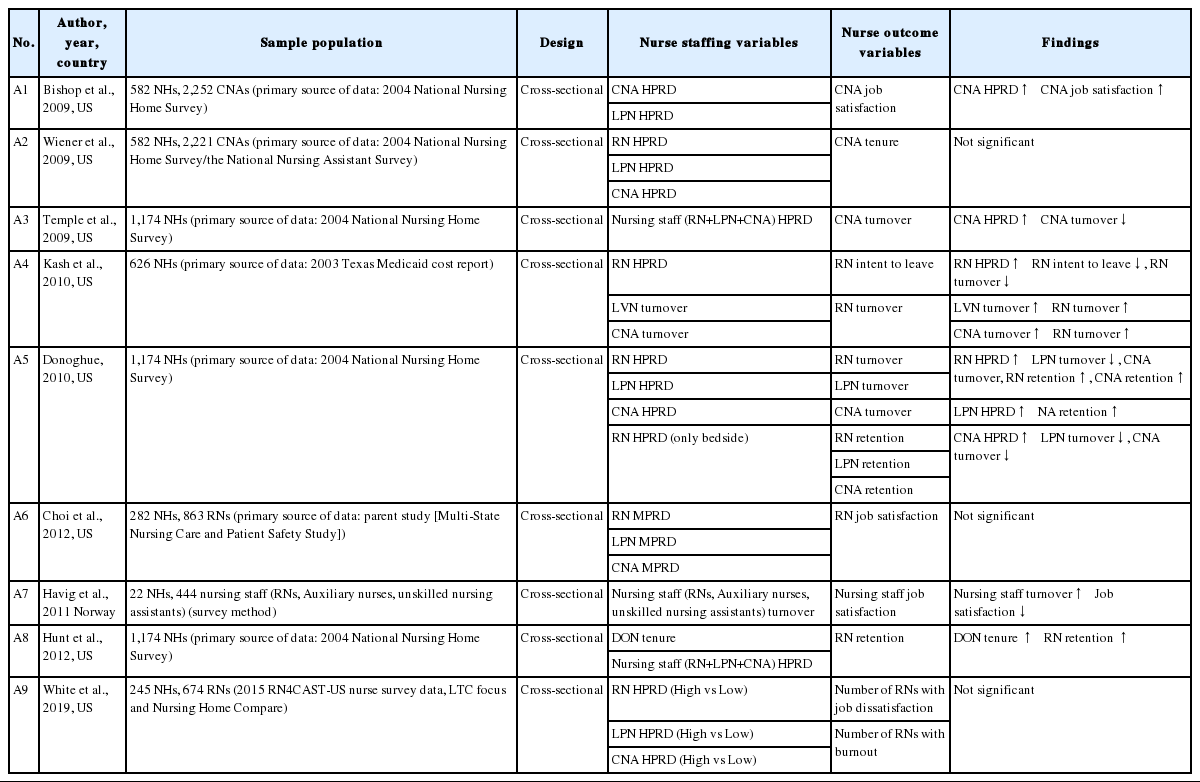

Findings from the included studies were summarized. The following data fields were extracted from the included studies: author, year, country, sample, setting, design, nurse staffing variables, nurse outcomes variables, and study findings (Table 1).

RESULTS

1. Study Characteristics

In this review, all studies used a cross-sectional design with observational study [A1-A9]. These observational studies used either a large database for a secondary analysis [A1-A6,A8,A9] or a survey method [A7]. One study used a large database from a parent study [A6]. Five studies used the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey data [A1-A3,A5,A8], and one study used the 2003 Texas Medicaid cost-report data [A4]. The unit of analysis in eight studies was NHs [A1-A6,A8,A9], with studies that used secondary data and the NH sample sizes ranged from 22 NHs to 1,174 NHs. The unit of analysis in one study was the individual nurse; that study used a survey method [A7].

In the process of reviewing the articles, the majority of literature on nurse staffing in NHs used HPRD to measure nurse staffing [A1-A5,A8,A9]. In addition, in previous systematic reviews on nurse staffing, researchers examined turnover rate, retention rate, and tenure in nurse staffing [A4,A7,A8]. In this review, the focus was on negative and positive aspects of nurse outcomes, including turnover rate, retention rate, intent to leave, job satisfaction, job dissatisfaction, and burnout.

2. Nurse Staffing Variables

In this review, three nurse staffing-related variables were identified. In studies included in this integrative review, researchers measured nurse staffing-related variables using HPRD (or minutes per resident day [MPRD]) or stability (turnover or retention). One study examined RNs at bedside HPRD only [A5]. Researchers measured nurse staffing stability by turnover rate [A4,A7] or nursing staff tenure [A8].

For nurse staffing, five of nine studies differentiated RNs from other nursing staff (LPNs, licensed vocational nurses [LVNs], CNAs, auxiliary nurses, and unskilled nursing assistants) [A4-A6,A9]. In a study conducted in Norway [A7], the distinction between nursing staff was different from that of the United States and included auxiliary nurses and unskilled nursing assistants but did not include LPNs and CNAs. Three studies used the term “total nursing staff”, without differentiating among types of nursing staff [A3,A7,A8], The remaining study included LPNs and CNAs only [A1]. Interestingly, one study assessed the tenure of the director of nursing (DON) [A8].

3. Nurse Outcome Variables

In this review, seven nurse outcome-related variables were identified. These variables were categorized into objective indicators and subjective indicators. Objective indicators included turnover rate, retention rate, and tenure. Subjective indicators included intent to leave, job satisfaction, job dissatisfaction, and burnout.

Turnover rate. In this review, turnover rate was used as a measure of nurse outcome in three studies [A3-A5]. Turnover rate is an objective indicator of the institutional unit that reflects a nurse’s individual turnover. One study examined a separate turnover rate of RNs, LPNs, and CNAs [A5], whereas other studies examined the turnover of either RNs [A4] or CNAs only [A3].

In a recent review of turnover methodologies, turnover was calculated as a ratio of less than one year to the total number of employees [10-12]. However, in this review, turnover rate was defined as the percentage of the total number of full-time-equivalent nursing staff who quit within 3 months [A3,A5]. Because longer time frames have been found to be less accurate, a 3-month time period was selected by the National Nursing Home Survey for enhanced reliability. Yet, in a study using Texas nursing-facility cost-report data, data for one year were used instead of data for 3 months [A4].

Retention rate. Retention rate is an indicator of staff stability. Retention rate is an objective indicator of the institutional unit that reflects a nurse’s individual retention. Retention rate is different from turnover rate because it reflects the propensity to remain on staff for a longer duration in the same facility [A5]. In this review, two studies emerged where researchers used retention rate as a nurse-outcome variable [A5,A8]. One study examined a separate retention rate of RNs, LPNs, and CNAs [A5], and one examined the retention of RNs only [A8].

Retention rate was calculated as the percentage of full-time equivalent nurses employed for more than one year [A5,A8]. Hunt et al. (2012) divided the retention of RNs into three categories because the distribution of a percentage of RN retention was non-normal: low (50% or less), moderate (51~79%), and high (80% or more) [A8].

Tenure. Job tenure is the length of time an employee has been employed by their current employer. In this review, CNA tenure was used as a nurse-outcome variable in one study [A2]. Wiener et al.(2009) used National Nursing Assistant Survey data, a survey of individuals rather than facilities, and thus used tenure as a nurse-outcome variable in the study [A2]. In this review, studies were divided into two groups: the whole CNA group and the CNA group with at least one year of job tenure at their NH [A2].

Intent to leave. One study measured RN’s intent to leave as a nurse outcome [A4], measured with two questions: intention to leave in the next 12 months and in the next 24 months [A4].

Job satisfaction. Three studies measured job satisfaction [A1,A6,A7] and one study measured job dissatisfaction [A9]. One study examined the satisfaction of RNs [A6], and one study examined the satisfaction of CNAs [A1]. One study examined the job satisfaction of all nursing staff (RNs, auxiliary nurses, and unskilled nursing assistants) without distinguishing between occupations [A7]. One study examined job dissatisfaction by calculating the number of nurses who were dissatisfied with their job [A9].

Burnout. Only one study examined the number of RNs with burnout [A9]. The researchers measured burnout using the Emotional Exhaustion Scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory [13].

4. Relationships between Nurse Staffing and Nurse Outcomes

Among eight studies that used HPRD (or MPRD) as nurse-staffing variables [A1-A6,A8,A9], four studies showed an association between increased HPRD (or MPRD) and better nurse outcomes [A1,A3-A5], whereas HPRD (or MPRD) was not statistically significant in the remaining four studies [A2,A6,A8,A9]. Specifically, higher HPRD (or MPRD) of RNs related to lower turnover rates of LPNs and CNAs [A4,A5], a higher retention rate of RNs and CNAs [A5], and a lower rate of RNs’ intent to leave [A4]. Also, higher CNA HPRD (or MPRD) was associated with a lower turnover rate of CNAs [A3] and higher job satisfaction among CNAs [A1].

Two studies examined the association between nursing-staff turnover and nurse outcomes. Higher turnover rate for LVNs and CNAs related to a higher turnover rate for RNs [A4]. Also, a higher turnover rate for total nursing staff (RNs, auxiliary nurses, and unskilled nursing assistants) related to lower job satisfaction of the entire nursing staff [A7].

One study used tenure as a nurse outcome [A2]. Wiener et al. (2009) investigated the relationship between nursing staff (RN, LPN, and CNA) and CNA tenure, but that relationship was not statistically significant [A2].

DISCUSSION

In a review of the last ten years of research in nurse staffing and nurse outcomes in NHs, it was found that better nurse outcomes aligned with higher levels of nurse staffing. Of the nine studies, six studies reported that an increased number of nursing staff and stable nurse staffing with more tenure and less turnover related to positive nurse outcomes in NHs [A1,A3-A5,A7,A8]. In contrast, three studies reported no relationship between nurse staffing and nurse outcomes [A2,A6,A9]. More stable nurse staffing included more DON tenure and lower nursing staff (RN, LPN, and CNA) turnover. However, some studies showed no relationship between nurse staffing and nurse outcomes [A2,A6,A9].

With respect to nurse staffing, lack of nursing staff resulted in an insufficient HPRD that prevents nurses from providing high quality of care. The American Health Care Association RN Manpower Survey found that 82% of NHs needed more CNAs, 76% were short of LPNs, and 71% were short of RNs [14]. Accordingly, in 2015, the U.S. government proposed new regulations about nurse staffing [15]. However, the proposed regulations do not require a change in the federal staffing standard. Considering that nurse-staffing levels relate not only to resident outcomes but also to nurse outcomes, appropriate nursestaffing levels should be identified for NHs.

None of the studies in this review considered ratios of RNs to all staffing levels. In addition to providing direct care to residents, RNs in NHs are responsible for multiple tasks, such as leadership and assistance to residents, staff supervision, recognizing significant changes in residents, and educating LPNs and CNAs [16]. However, most NHs hire CNAs rather than RNs due to financial pressures [17]. Because the responsibilities and roles of each nursing staff level are different, the roles distributed to each nursing staff member and the consequences (nurse outcomes) may vary, depending on the proportion of each nursing profession. Therefore, in future studies, skill mix as a factor related to nurse outcomes should be considered.

A high RN turnover rate is a major concern for NH nurses and residents because many studies and government reports have addressed the issue of adverse outcomes resulting from higher RN turnover rates [18,19]. Researchers reported that nursing turnover links to other staff turnover and poor quality of care in NHs [A4,18]. Also, the turnover of nursing staff leads to increased costs for facilities in recruitment, training, selection, and supervision of new nursing staff [20]. Adequate nurse-staffing levels should be addressed to improve resident outcome and RN retention.

NHs have remarkably low RN-retention rates. Although recent data is lacking, in 2004, the retention rate of RNs at NHs in the United States was reported to be 67.3% [A8]. The tenure of RNs in Korea’s NHs in 2016 was reported to be 2.2 years [21]. The difference in the retention rates and tenure of RNs between the United States and Korea is due to the difference in the work environment. In the United States, an elder-care expert panel in Hartford in 2000 required at least one RN for every 15 residents on the day shift, one for every 20 residents on the evening shift, and one RN for every 30 residents on the night shift. Also, the median RN HPRD in the United States is 4 hours 25 minutes [5]. Korea’s nurse-staffing standards are significantly lower than those of the United States. The legal requirement for nurse staffing in Korea is that each NH should deploy one RN (or CNA) for every 25 residents, regardless of shift. This is 18 minutes, when converted into HPRD. Also, only 1,472 RNs are deployed in NHs, whereas 7,806 CNAs and 64,179 care workers are deployed in NHs in Korea [1].

To increase the retention rate and tenure among RNs, a positive work environment should be created through adequate nurse staffing (higher staffing and higher RN skill mix). Studies are needed on RNs’ working environments in NHs to improve resident health outcomes because high tenure affects other nursing-staff retention [A8] and will ultimately result in seamless, high-quality care. Organizational efforts are needed to create a positive work environment.

A gap exists in the current state of NH literature. The parameters measured as outcomes of nurses are limited. In a study of hospital nurse staffing and nurse outcomes, researchers measured parameters such as emotional exhaustion, stress, and needlestick injuries as nurse outcomes [22]. More diverse outcome variables should be identified and measured in studies of nurses working in NHs. Additionally, all nine studies used a cross-sectional design. As a result, it is not possible to establish causality between nurse staffing and nurse outcomes. Research design may be why studies did not find significant relationships between nurse staffing and nurse outcomes. Future studies should be conducted using longitudinal designs to explain causality. Finally, in this review, most (88.9%) studies were conducted in the United States, thereby limiting generalizability.

This review has several limitations. First, although a comprehensive search strategy was used in this study, the search terms used for nurse staffing and nurse outcomes may not capture all possible terms indicating nurse staffing and nurse outcomes in publications in this area. Therefore, future studies involving all studies related to this area are needed. Second, the measurement of nurse staffing, nurse outcomes, and study samples varied dramatically. This wide variety made it impossible to compare the rate of change in nurse outcomes across studies. Third, the limited number of included studies may limit the ability to explain variation in the relationship between nurse staffing and nurse-outcome measures.

Despite these limitations, this review provides important evidence that nurse staffing relates to nursing outcomes such as turnover rate, retention rate, intent to leave, and job satisfaction. Results from this review provide preliminary information to identify appropriate nurse-staffing levels to improve positive nurse outcomes and residents’ health and wellness. A need persists for continued research to examine the effects of increased nurse staffing on short-term and long-term NH resident health outcomes to provide guidance on nurse-staffing policy for NHs.

CONCLUSION

Data from this review provide preliminary evidence that nurse staffing (number and stability) in NHs is associated with nursing outcomes such as turnover rate, retention rate, intent to leave, and job satisfaction. Future research needs to be conducted that includes more diverse variables than nursing staff and nursing outcomes such as nursing error, emotional exhaustion, burnout, and stress. Through this review of studies related to NH nurse staffing and nurse outcomes, study results can help health care professionals, researchers in practice, administrative staff, researchers, and politicians establish strategies for nurse staffing to prevent adverse nurse outcomes. These results can also provide evidence of the importance of nurse staffing in NHs and lead to more effective deployment of nursing staff and help for NHs’ nurse-staffing policies.

Future research is necessary to derive more causative research results through intervention studies or longitudinal studies on nurse outcomes, based on nurse staffing. Based on these findings, research should be conducted to estimate the appropriate level of nursing staff to improve nurse outcomes.

Notes

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Study conception and design acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, and final approval - LJ.