The impact of Long COVID, work stress related to infectious diseases, fatigue, and coping on burnout among care providers in nursing home: A cross-sectional correlation study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

An increasing number of nursing home are being established because of the increased demand for treatment and care of older adults with chronic diseases related to population aging. This study aimed to examine the impact of long COVID, infectious diseases-related to work stress, fatigue, and coping on burnout among care providers in nursing home during the persistent COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A total of 168 care providers, including nurses, nursing assistants, and caregivers working in nursing home between July 22 and August 12, 2022 were polled by a questionnaire survey. The collected data were analyzed using an independent t-test, one-way analysis of variance, Scheffé test, Pearson correlation coefficient, and multiple regression analyses via SPSS 21.0.

Results

The prevalence of Long COVID-19 among care providers in nursing home was 85.7%, with a mean burnout score of 2.59 out of 5. Work stress related to infectious diseases (β=.27, p=.002) and infection control fatigue (e.g., fatigue related to complexity of nursing duties and shortage in employees [β=.51, p=.019], conflicts caused by uncertain situations and a lack of support [β=.50, p=.012]) were the variables that significantly associated with burnout.

Conclusion

It is crucial to actively explore strategies for reducing overall work stress, anxiety, and fatigue, particularly related to infection management to alleviate burnout among care providers in nursing home. Our findings provide fundamental data for the development of interventions and policies to prevent care providers’ burnout, thus enabling the provision of high-quality care in nursing home.

INTRODUCTION

As of May 13, 2023, South Korea has reported a total of 31,390,699 confirmed coronavirus (COVID-19) cases and 34,597 deaths. Of these, 32,406 deaths occurred among individuals aged 60 years or older, accounting for 93.7% of all deaths. Older adults, particularly those residing in nursing home and facilities, have been vulnerable to outbreaks [1]. COVID-19 is characterized by its ability to spread quickly in enclosed and crowded environments, placing caregivers in nursing home at a high risk of infection because of their exposure to facility conditions, such as high occupancy rates, narrow bed-to-bed distances, frequent physical contact with clients, and shared meals [2]. Many patients diagnosed with COVID-19 have reported symptoms that persist after the acute phase of COVID-19. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has termed these post-COVID conditions as “chronic COVID-19 syndrome” or “Long COVID”, defined as symptoms that persist for weeks following the initial COVID-19 infection. Common symptoms of Long COVID include fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, heart palpitations, headaches, sleep issues, dizziness, and changes in smell or taste [3,4].

Burnout refers to a state of psychological, emotional, and physical exhaustion that affects both individuals and organizations. More than half of hospital workers experience burnout, which raises serious concerns because it reduces the quality of patient care and productivity, and can even lead to relationship breakdowns and suicide [4]. Although data on the prevalence of Long COVID among care providers in nursing home are unavailable, a study in the United Kingdom found that approximately 36% of healthcare workers experienced Long COVID, with 57% experiencing burnout, indicating a correlation between the two [5]. In addition, the care and support responsibilities of care providers in nursing home frequently lead to high levels of job stress due to various work-related factors, emotional strain, and a lack of self-care, all of which have been shown to contribute to burnout [6]. Notably, during the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers have been experiencing high levels of fatigue and burnout, with fatigue serving as a predictor of burnout [7]. Coping mechanisms play a crucial role in managing burnout among healthcare workers. Coping is a continuously evolving set of cognitive and behavioral changes aimed at managing an individual’s perceived internal and external demands, and it serves as a strategy to mitigate burnout in healthcare workers [8].

Given that the quality of care and treatment provided by care providers in nursing home is closely related to their psychosocial health, it is important to pay attention to their mental health and well-being [9]. In nursing home, care is primarily provided by nurses, nursing assistants, and caregivers. Nursing assistants and caregivers provide direct care for older patients, while nurses are primarily responsible for educating and supervising them [10]. Providing care in nursing home involves inherent tension, arising from caring for physically disabled or dementia-affected older adults, accompanied by the burden of addressing various issues related to the care for older individuals [9-11]. As nursing home are expanding owing to rapid population aging, burnout among care providers in this care setting is on the rise. While studies on burnout have been conducted at home and abroad, most have focused on healthcare workers such as nurses and doctors [5-7,10-15]. There is a lack of research on burnout among care providers in nursing home in Korea, where COVID-19 outbreaks are frequent.

In particular, very few domestic studies have examined the relationship between Long COVID, infectious disease work stress, infection control fatigue, coping, and burnout among nursing home care providers. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the prevalence of Long COVID among care providers in nursing home and analyze the effects of Long COVID, work stress related to infectious, infection control fatigue, and coping mechanisms on burnout. The findings may provide a basis for developing effective strategies to reduce burnout among care providers nursing home and for long-term COVID-19 management in the future.

1. Objectives

This study aims to explore the impact of Long COVID, work stress related to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, and coping on burnout among care providers in nursing home. The specific objectives of this study are as follows:

To determine the prevalence of Long COVID among care providers nursing home and identify their levels of work stress related to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, coping, and burnout.

To identify the factors that contribute to burnout among care providers in nursing home.

METHODS

Ethic statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jeonbuk National University (IRB No. 2022-06-037-001). Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

1.Study Design

This cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the impact of Long COVID, work stress related to infectious, infection control fatigue, and coping on burnout levels among care providers in nursing home.

2. Theoretical Framework

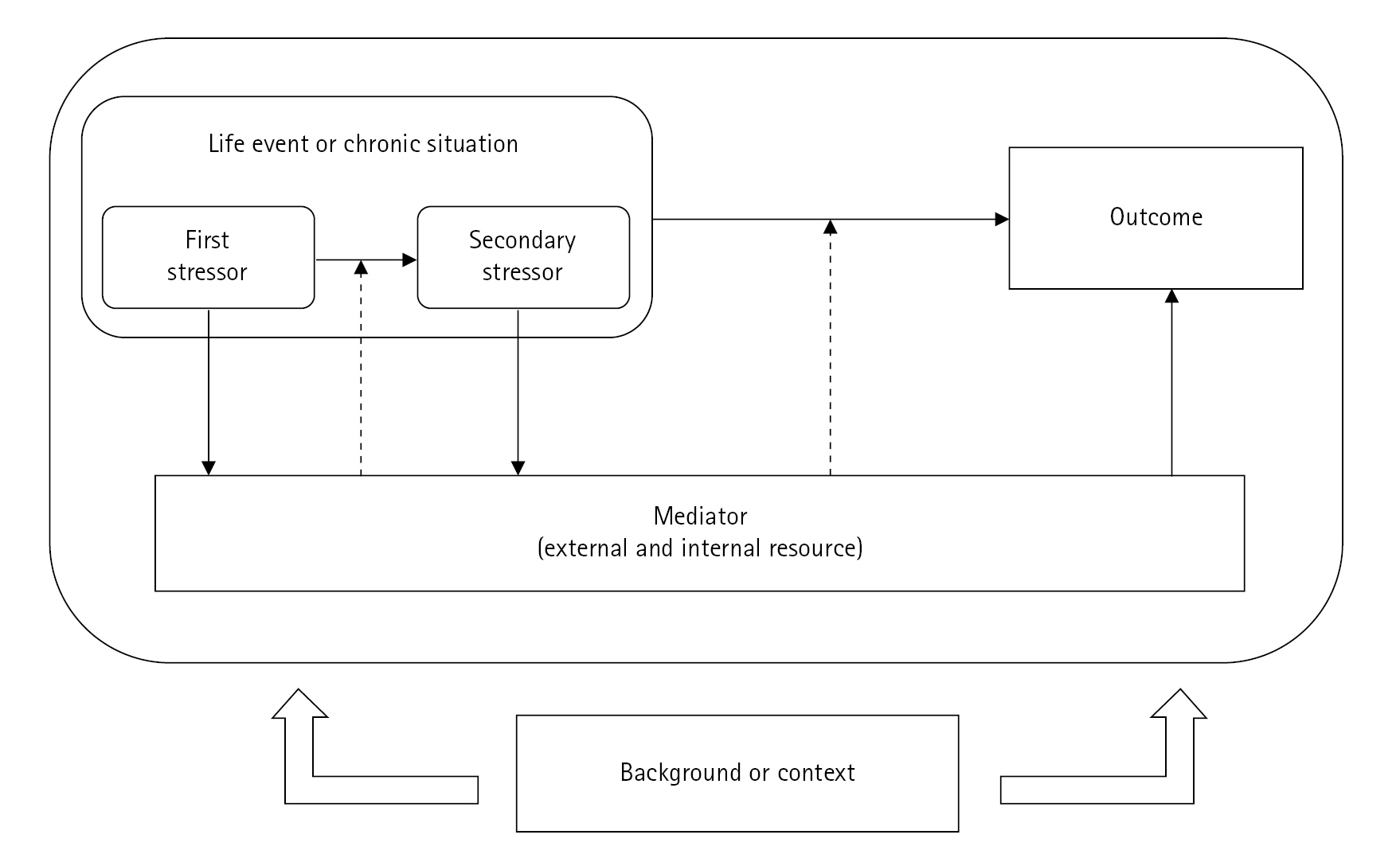

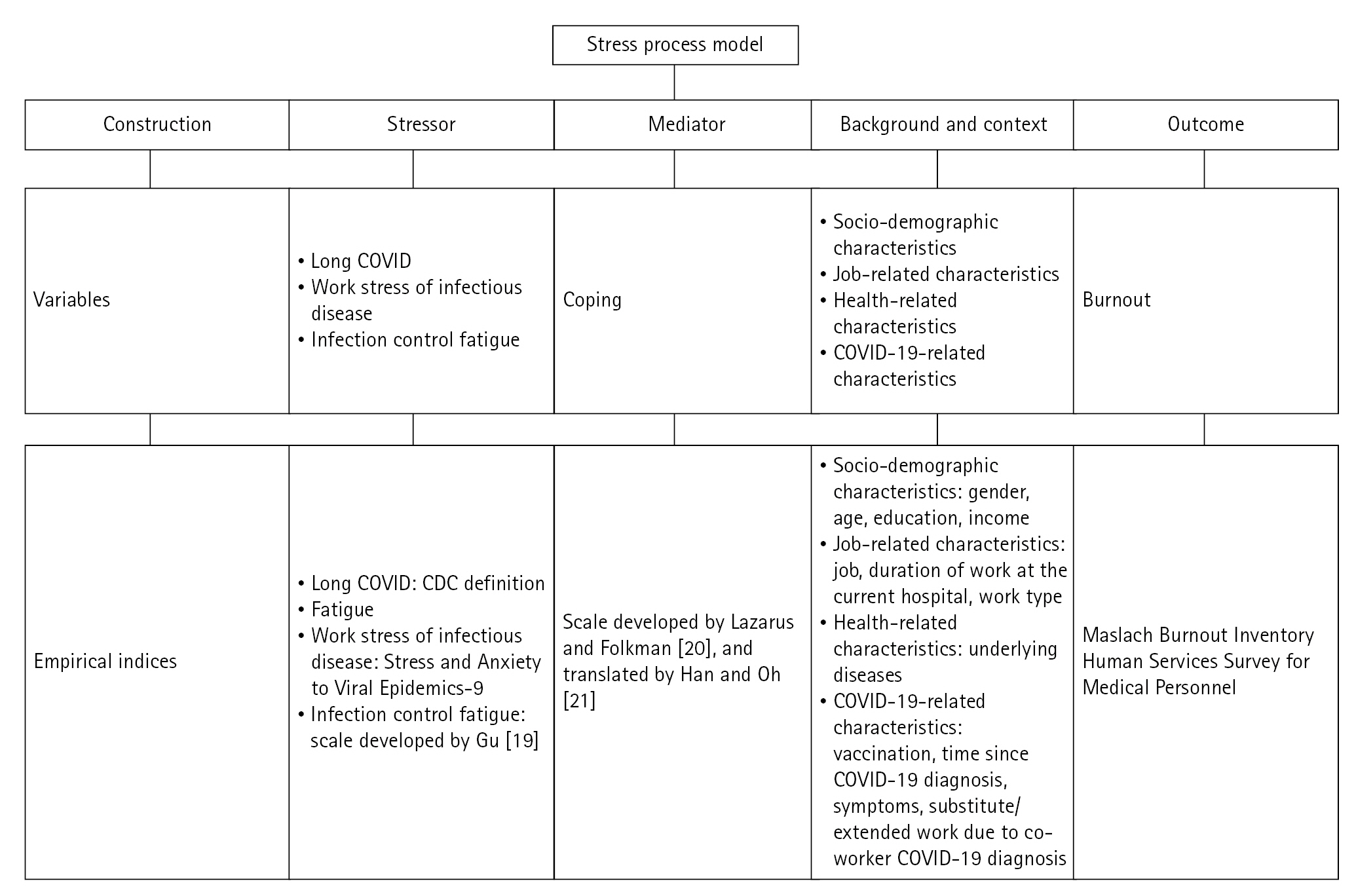

This study utilized the stress process model as a theoretical framework that explains mental health issues such as burnout, and consists of stressors, mediators, contextual, background, and outcome factors (Figure 1). Based on the stress process model and previous studies [4-6,8,10,12,13], this study included burnout as an outcome factor, with Long COVID, infectious disease-related work stress, infection control fatigue, and coping as a mediating factor. It also considers demographic (gender, age, education, and income), job-related (type of job, duration of work at the current hospital, and type of work), and health-related (underlying diseases) characteristics, as well as COVID-19-related (vaccination, time since COVID-19 diagnosis, symptoms, and substitute/extended work due to co-worker’s COVID-19 diagnosis) characteristics as contextual factors [16] (Figure 2).

3. Study Participants

The target population comprised care providers working in nursing home in Korea, including nurses, nursing assistants, and caregivers, who provided care for older patients in four nursing home located in Jeonbuk Province. As the study focused on burnout among nursing home care providers who provided direct care to older adults, physical therapists and social workers were excluded. The inclusion criteria consisted: 1) those who had worked in a nursing home for more than 1 year, 2) those aged 18 years or older, 3) nurses, nursing assistants, and caregivers who were directly involved in patient care, 4) those who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 for more than 4 weeks, 5) those who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study, and 6) those who understood the study content and were able to complete the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria comprised those who were asymptomatic when diagnosed with COVID-19 and those with a psychiatric history.

Participants were selected using convenience sampling from four nursing home in Jeonbuk Province. Data were collected using a questionnaire, and only participants who expressed their willingness to participate were recruited.

To calculate the sample size, the G*Power version 3.1 program was utilized with an effect size of .15, a significance level of .05, power of .80, and 17 predictor variables, which required a minimum of 146 participants. Considering a dropout rate of approximately 20%, data were collected from 183 participants. The data from a total of 168 participants were used in the final analysis after excluding participants who were not nurses, nursing assistants, or caregivers (n=5), provided insufficient answers (n=4), had been diagnosed with COVID-19 for less than 4 weeks (n=4), and were asymptomatic at diagnosis (n=2).

4. Research Instruments

The research instruments used in this study were approved by their respective developers. A pilot test was conducted with 15 nurses, nursing assistants, and caregivers (five each) to assess their understanding of the questions and the time required to complete the final questionnaire. The results indicated that the time to complete the questionnaire ranged from 10 to 30 minutes, with an average time of 13.6 minutes, and all participants found the questions easy to understand.

1) Burnout

Burnout was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel developed by Maslach and Jackson [17]. The instrument consists of three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment, measured on a 22-item, 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all, 5=very much). For ease of interpretation, the personal accomplishment items were reverse-transformed and analyzed, with higher total scores indicating higher burnout levels. In the original instrument development study [17], the Cronbach’s ɑ was reported to be .84, while in this study, the Cronbach’s α was .87.

2) Long COVID

In this study, Long COVID was defined in accordance with the CDC definition as the persistence of symptoms beyond 4 weeks of COVID-19 diagnosis [3]. Participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced any of the 23 symptoms reported by the CDC. Each symptom experienced was coded as 1 if the respondent answered “Yes” and 0 if the respondent answered “No”, and the scores for all 23 questions were summed. A total score of 0 indicated no experience of Long COVID, whereas a score of 1 or higher indicated the presence of Long COVID. A higher total score indicated a greater number of Long COVID symptoms reported by the participant.

3) Work stress related to infectious diseases

To measure work stress related to infectious diseases, this study employed the 3-item Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 scale developed by the Seoul Asan Medical Center [18], specifically corresponding to the ‘work stress’ subscale. The scale was measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all, 5=very much), with higher scores indicating higher levels of work stress related to viral epidemics. At the time of development, the Cronbach’s α was reported to be .79, and in this study, Cronbach’s α was .67.

4) Infection control fatigue

Infection control fatigue was measured using the infection control fatigue scale developed by Gu [19]. The scale consists of 39 items organized into five subdomains: exhaustion related to complexity of nursing duty and shortage in employees, deterioration of patients’ conditions and lack of knowledge, conflicts caused by uncertain situation and lack of support, concerns on infections and burden caused by excessive amount of attention, and conflict and lack of support due to uncertainty, burden factors due to infection concerns and excessive attention, and new roles and demands. Each item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all, 5=very much), with higher scores indicating higher levels of COVID-19 infection control fatigue. In Gu’s study [19], the Cronbach’s α was .96, and Cronbach’s α was .98 in the current study.

5) Coping

Coping was measured using an instrument developed by Lazarus and Folkman [20] and translated by Han and Oh [21]. It comprises 33 items and six subscales, including problem focus, wishful thinking, apathy, seeking social support, positive perspective, and relaxation. Each item was measured on a 4-point Likert scale (1=not at all, 4=very much), with higher scores indicating greater use of various coping methods. In Han and Oh’s [21] study, Cronbach’s α was .79, and in this study, Cronbach’s α was .86.

6) General characteristics

The general characteristics of the participants included demographic, job-related, health-related, and COVID-19-related characteristics. Demographic characteristics included information on gender, age, education, and income. Job-related characteristics included type of job, duration of work at the current hospital, and work type. Health-related characteristics included information on whether the participants had any medical conditions. COVID-19-related characteristics included information on COVID-19 vaccination status, time since COVID-19 diagnosis, symptoms of COVID-19 infection, and whether they had to work alternative or extended hours due to co-worker’s COVID-19 diagnosis.

5. Data Collection

Data collection was conducted from July 22 to August 12, 2022, among nurses, nursing assistants, and caregivers working in four nursing home in Jeonbuk Province. The study’s purpose, content, and participation methods were explained to the nursing directors of each hospital. After obtaining their cooperation and approval, a recruitment notice was posted on the staff bulletin board. The nursing director of each hospital distributed the questionnaires and informed consent forms to staff members who expressed their willingness to participate. The completed questionnaires were sealed in a paper envelope and placed directly in a designated collection box in each nursing home.

The participants completed the structured questionnaire manually, which took approximately 20 minutes to complete. A small gift (a travel toothbrush set) was offered as compensation for their time.

6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the IRB of Jeonbuk National University University (IRB No 2022-06-037-001).

7. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 21.0; IBM Corp.). General characteristics, Long COVID experience, work stress related to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, coping, and burnout were analyzed using frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Differences in burnout levels according to general characteristics were analyzed using an independent t-test and analysis of variance, followed by post-hoc tests using the Scheffé test. The correlations among Long COVID, work stress related to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, coping, and burnout were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. To examine the factors contributing to burnout among the participants, we performed a regression analysis. The analysis included education, job type, and the count of symptoms during COVID-19 diagnosis as control variables. Additionally, Long COVID, work-related stress linked to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, and coping were considered as independent variables. The dependent variable was burnout. Education and job type, both measured nominally, were treated as dummy variables, with middle school graduates and caregivers as the respective baseline values.

RESULTS

1. Differences in Burnout Based on General Characteristics of Participants

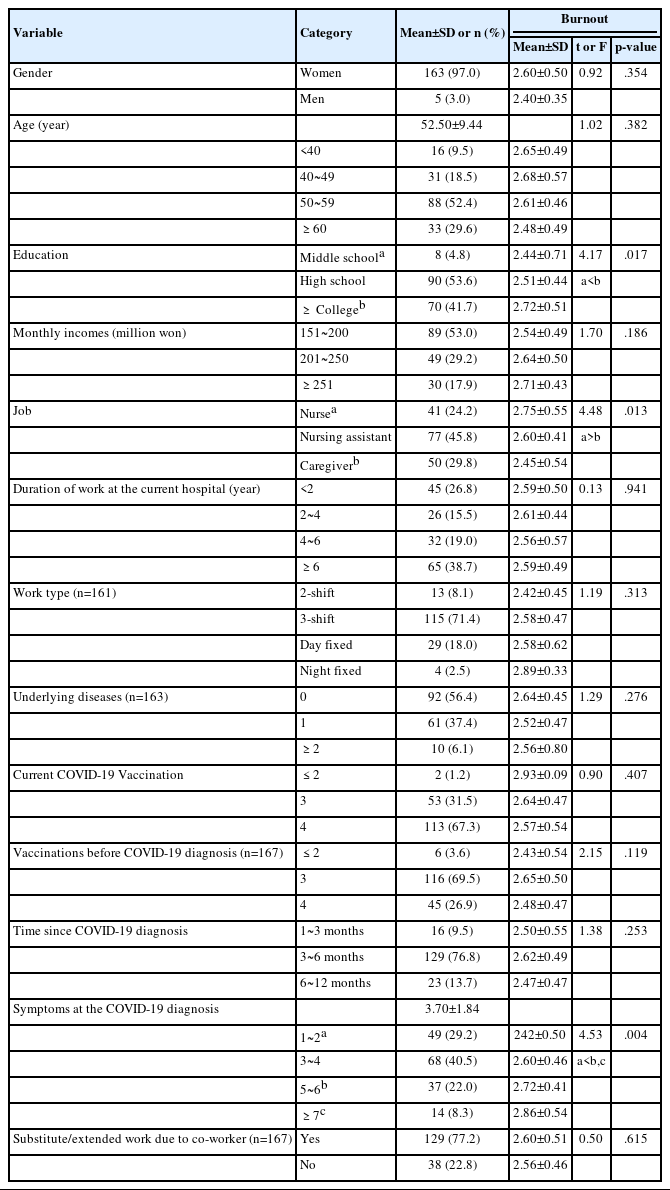

The general characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Among the study participants, 163 (97.0%) were women, with a mean age of 52.50±9.44 years. As for education, 90 (53.6%) graduated from high school, and 89 participants (53.0%) had a monthly income between Korean Won (KRW) 1,510,000 and KRW 2,000,000. In terms of job-related characteristics, 77 (45.8%) were nursing assistants, 65 (38.7%) had been working at their current nursing home for more than 6 years, and 115 (71.4%) were three-shift care providers. Regarding health-related characteristics, 92 (56.4%) had no medical conditions, while 61 (37.4%) had one medical condition. Regarding COVID-19-related characteristics, 113 participants (67.3%) had received four COVID-19 vaccinations at the time of their recent diagnosis. At the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, 116 (69.5%) had received three vaccinations. One-hundred twenty-nine (73.8%) reported that the time since their COVID-19 diagnosis was 3~6 months. The average number of symptoms at the time of diagnosis was 3.70±1.87, and 129 participants (77.2%) reported working substitute or overtime shifts due to a coworker’s COVID-19 diagnosis (Table 1).

Participants’ burnout levels varied significantly based on education (F=4.17, p=.017), type of job (F=4.48, p=.013), and the number of symptoms at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis (F=4.53, p=.004). Nurses had higher levels of burnout than caregivers, as did those with a college degree or higher than those with a middle school degree. In addition, participants with five or more symptoms at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis exhibited higher levels of burnout than those with two or fewer symptoms (Table 1).

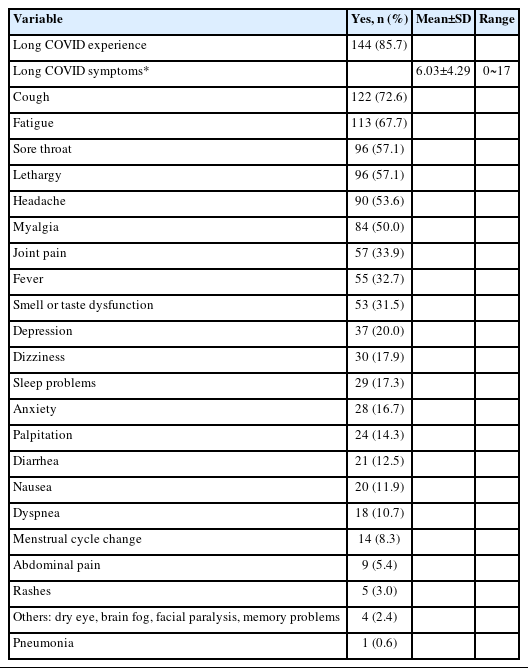

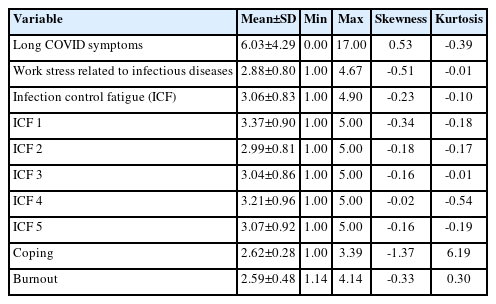

2. Participants’ Experience of Long COVID, Work Stress Related to Infectious Diseases, Infection Control Fatigue, Coping, and Burnout

Of the total participants, 144 (85.7%) reported having Long COVID, with an average of 6.03±4.29 symptoms. Cough was the most commonly experienced symptom, reported by 122 participants (72.6%). Other frequently reported symptoms included fatigue (n=113; 67.7%), sore throat (n=96; 57.1%), lethargy (n=96; 57.1%), and headache (n=90; 53.6%). The symptoms experienced less frequently included pneumonia (n=1; 0.6%), other unspecified symptoms (n=4; 2.4%), rashes (n=5; 3.0%), and abdominal pain (n=9; 5.4%) (Table 2). The mean score for work stress related to infectious diseases was 2.88±0.80. The overall mean score for infection control fatigue was 3.06±0.83, with subscales of complex procedures and staffing shortages at 3.37±0.90 and burdened by infection concerns and excessive attention at 3.21±0.96. Coping had a mean score of 2.62±0.28, and burnout had a mean score of 2.59±0.48. The skewness and kurtosis of the data were also examined. The skewness values ranged from -1.37 to 0.53, while the kurtosis values ranged from -0.54 to 6.19, with a skewness value of 3 and a kurtosis value of 10 fulfilling the assumption of normality of the data (Table 3).

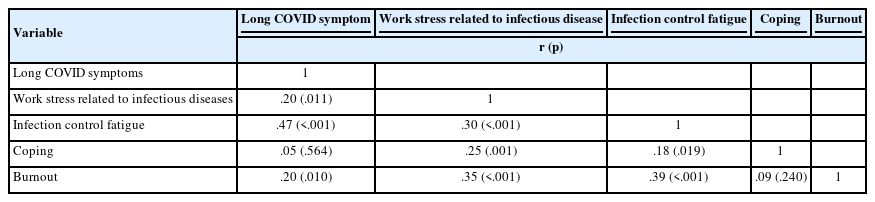

Regarding the relationship between the number of Long COVID symptoms, work stress related to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, coping, and burnout, the findings indicated that burnout was positively and significantly correlated with the number of Long COVID symptoms (r=.20, p=.010), work stress related to infectious diseases (r=.35, p<.001), and infection control fatigue (r=.39, p<.001). In contrast, burnout and coping (r=.09, p=.240) were not significantly correlated (Table 4).

3. Factors Influencing Burnout

Among the independent variables, coping was not found to be significantly related to burnout in the univariate analysis. However, as coping is a significant factor in the stress process model, which forms the theoretical basis of this study, it was included in the multivariate analysis.

Before running the regression, we checked whether the underlying assumptions were satisfied, and we found that all assumptions were met. The normality of the residuals was confirmed as the scatterplot closely resembled a 45° straight line. Linearity and homoscedasticity assumptions of the model were satisfied, as the residuals were evenly distributed around zero. The autocorrelation of the dependent variable was checked using the Durbin-Watson index, which was 2.13, indicating that the residuals were independent without autocorrelation. In addition, the variation inflation factor ranged from 1.15 to 7.96, which did not exceed 10, indicating no multicollinearity among the independent variables. Furthermore, the regression model fit was significant (Table 5).

The regression analysis indicated that the major factors influencing burnout were work stress related to infectious diseases (β=.27, p=.002), the sub-domain of infection control fatigue related to complexity of nursing duty and shortage in employees (β=.51, p=.019), and the sub-domain of conflicts caused by uncertain situation and lack of support (β=.50, p=.012), with an explanatory power of 23.7% (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

By examining the prevalence of Long COVID among care providers in nursing home who were on the frontlines of patient care and support during the COVID-19 outbreak and the impact of work stress related to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, and coping on burnout, this study attempted to provide a foundation for managing burnout during the prolonged COVID-19 period. The major factors influencing burnout were work stress related to infectious diseases, the sub-domain of infection control fatigue related to complexity of nursing duty and shortage in employees, and the sub-domain of conflicts caused by uncertain situation and lack of support.

The prevalence of Long COVID in this study was found to be 85.7%, while the average number of symptoms reported by participants was more than six. The most common symptoms were cough, fatigue, lethargy, sore throat, headache, and muscle pain. This finding is similar to the results of a study conducted by Yong [22], which examined symptoms after COVID-19 in countries such as the United Kingdom, Italy, and Australia and found that the prevalence of Long COVID ranged from 38.7% to 87.4% across different countries, with similar symptoms such as cough, fatigue, sore throat, lethargy, and shortness of breath. Therefore, it is necessary to closely monitor the symptoms of nursing home care providers with Long COVID given its high prevalence, and special attention should be given to the potential occurrence of complications. To this end, it is crucial to offer assistance in managing post-effects, as well as educating nursing home care providers about tailoring their daily routines to individual circumstances, thereby empowering them to engage in effective self-care practices.

The average score of work stress related to infectious diseases among the participants in this study was 2.88 out of 5. The stress related to infectious diseases was examined in a study [10] focusing on acute-stage nurses responsible for newly admitted patients with infectious diseases. The recorded stress level was 3.45, surpassing the findings of our current study. While caregivers in acute hospitals attend to moderately ill patients for brief durations, those in nursing home are tasked with consistently managing stress due to caring for older patients with chronic diseases, including cases of COVID-19. Considering that nursing home care providers are constantly exposed to COVID-19 infections, they are burdened with intense workloads for long periods, along with anxiety about infection risks, resulting in increased physical and mental stress [23]. A study on the stress experienced by nurses working in COVID-19 inpatient wards [24] found that job stress and turnover intention increased in the context of dealing with new infectious diseases. Therefore, it is necessary to establish clear infectious disease work protocols for nursing home during new epidemics, provide comprehensive response training to help nursing home care providers adapt to infectious disease work, support the expansion of rest areas, and improve convenience measures to reduce work-related stress.

The participants reported an average infection control fatigue score of 3.06 out of 5, with higher fatigue levels noted in the subcategories of complexity of nursing duty and shortage in employees, conflicts caused by uncertain situation and lack of support. This finding is somewhat lower than that found in a study among general hospital nurses caring for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic [10], which reported a fatigue score of 3.45, but it still indicates a moderate-to-high level of fatigue. This difference in scores may be due to disparities in the characteristics of healthcare organizations and the general characteristics of the people being cared for. Among the subcategories, complexity of nursing duty and shortage in employees indicated the highest levels of fatigue, which is consistent with previous research on caring for patients with respiratory infections [15]. Healthcare workers on the frontline during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced more multifaceted fatigue than those caring for the general population owing to fear of contagion, unfamiliar tasks, and frequently changing quarantine guidelines [24]. Furthermore, the deteriorating health of care recipients due to COVID-19 has increased the workload and intensity for healthcare and care facility workers, leading to prolonged tension-related fatigue [23,25].

Coping of nursing home care providers, as parameterized in this study through the stress process model, scored 2.62 out of 4, indicating their ability to cope with burnout within their work environment. A study on clinical nurses [25] during the COVID-19 pandemic using the same instrument as in this study, reported a similarly moderate coping score of 2.67. An emerging infectious disease pandemic, such as COVID-19, may contribute to a decrease in coping capacity, leading individuals to perceive the situation as beyond their control [21,25]. Therefore, national preparedness and robust response strategies are required to prevent and reduce burnout among healthcare workers who provide care to susceptible populations during an infectious disease outbreak such as COVID-19, in addition to improving individual coping skills.

The mean burnout score in this study was 2.59 out of 5 (39.8 on a 100-point scale). A study on nurses in Korean general hospitals during the initial COVID-19 pandemic [11] reported a burnout score of 30.0, while a study on nursing home caregivers in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic [26] reported a burnout score of 31.9. The factors contributing to this higher mental and physical burnout in nursing home include the high risk of outbreaks in such vulnerable facilities, the high level of tension experienced by nursing home care providers, and the potential severe outcomes, such as patient deaths due to infectious diseases [12]. As burnout among nursing home care providers can reduce the quality of care provided to patients and increase workers’ turnover intentions [13], it is important to strengthen disaster response capabilities for new infectious disease epidemics. This can be achieved by implementing appropriate job-oriented regulations and conducting regular simulation training for nursing home care providers before the outbreak of infectious diseases so that they can respond appropriately and mitigate the impact of burnout.

Based on a stress process model, this study examined the impact of Long COVID, work stress related to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, and coping on burnout. The results indicated that burnout levels increased when participants experienced higher levels of work stress related to infectious diseases and infection control fatigue, compared to complexity of nursing duty and shortage in employees, conflicts caused by uncertain situation and lack of support. Several previous studies [11,18] have also shown that higher levels of burnout were associated with increased anxiety and stress related to infectious diseases, and that continued exposure to work anxiety, stress, and burnout eventually results in turnover and resignation among healthcare workers. Infection control fatigue related to healthcare workforce shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic has increased burnout levels among nurses in the United States [26] and Korean nurses caring for patients with respiratory infections [15]. Therefore, to reduce burnout among care providers in nursing home, proactive efforts to reduce infection control fatigue, which is exacerbated in healthcare settings where caregivers provide face-to-face care for vulnerable patients, remain a priority. One crucial measure is the establishment of clear protocols for care provision. In addition, government policies should include practical and reasonable support measures, such as the recruitment of additional personnel and the utilization of care assistants to address the labor shortage problem at the frontline.

One of the strengths of this study is the systematic consideration of various influencing factors. The stress process model, which is widely used in the literature and mental health research, encompasses stressors, mediators, contextual, background, and outcome factors. This study found that the “stressors” of infection-related work stress and fatigue, rather than demographic, occupational, or COVID-19-related factors suggested by the stress process model, were the most influential factors contributing to nursing home care providers’ burnout. Therefore, stress-reduction strategies should be implemented to reduce burnout among care providers in nursing home. Further research is required to identify other sources of stress, in addition to infection-related work stress and fatigue, to expand the understanding of nursing home care providers’ experiences. Although coping was found to be correlated with burnout as a mediator, the regression analysis showed that the two variables were not statistically significant. This suggests that the effectiveness of coping may not always be fixed but could depend on the situational context in which stress is experienced [20]. In addition, the emergence of COVID-19 variants and the prolonged pandemic may have led to changes in individuals’ ability to cope with problematic situations. Therefore, it is important to conduct replication studies on the impact of coping on burnout as the COVID-19 pandemic comes to an end.

Although the present study reveals important findings, it has several limitations. First, the study was conducted with care providers in local nursing home, which may limit the generalizability of the results to all nursing home care providers in Korea. In addition, there could be biases in the findings as participants recalled their experiences with COVID-19 symptoms through a self-administered questionnaire. In addition, the majority of care providers in this study were women, which may influence the results. Therefore, future research should consider the influence of gender.

However, this study is significant in that it identified the prevalence of Long COVID among nursing home care providers and the factors influencing burnout in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially with the emergence of the omicron mutation and recurrent outbreaks. The study also serves as a basis for developing programs aimed at preventing and managing burnout among nursing home care providers in the event of new infectious diseases. A core strength of this study is that it examined the effects of infection control fatigue and work stress related to infectious diseases on burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic using measures specifically related to infection control.

CONCLUSION

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of Long COVID among nursing home care providers in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the factors contributing to burnout, including work stress related to infectious diseases, infection control fatigue, and coping. The results showed that work stress related to infectious diseases and infection control fatigue caused by complicated procedures, conflicts due to staff shortages and uncertainty, and lack of support significantly contributed to burnout.

While patient-facing infection control work is critical, care providers in nursing home without negative-pressure rooms continue to work overtime, leading to high levels of stress and fatigue in their efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19 infection. Therefore, to reduce burnout among care providers of vulnerable populations, it is essential to develop a comprehensive plan that thoroughly prepares care providers in nursing home for an infectious disease pandemic. In addition, the roles for infection prevention in medical institutions and facilities should be systematically defined. Moreover, it is necessary to provide sufficient education and training to reduce overall work stress and fatigue, including infection control measures. Active support and multifaceted measures, such as ensuring rest breaks, guaranteed working hours, and hiring additional personnel to alleviate the workload burden on care providers, should also be implemented.

In conclusion, this study serves as a foundation for establishing effective interventions and policies to prevent burnout among care providers who provide care to vulnerable populations during emerging infectious disease outbreaks in the future. As the number of nursing home continues to increase owing to the demand for treatment and care due to rapid population aging and the increase in the number of older patients with chronic diseases, it is crucial to address the unique challenges faced by care providers, including burnout.

Notes

Authors' contribution

Study conception - JP, YS, and YY; Data collection - YS; Analysis and interpretation of the data - JK, HL, YY, and JP; Drafting and critical revision of the manuscript - HL, JK, HYS, JP, and YY; Final approval - YY, HL, and JK

Conflict of interest

No existing or potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of the Academic Research Support Project of the Jeonbuk Chapter of the Korean Gerontological Nursing Association.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Acknowledgements

None.