INTRODUCTION

The middle–old-aged group, which encompasses individuals aged 50 years and over, is fundamentally in a pivotal phase in their life cycle. At this stage, their child-rearing responsibilities typically end. At the same time, the care for older parents becomes their new primary concern, thus illustrating a caregiving shift from their children to parents [1]. Nevertheless, due to demographic changes, such as societal aging and the growing economic participation of women, this age group often extends their caregiving role to their older parents, grandchildren, and even single or unmarried adult children [2]. The middle–old-aged group includes cases where the caregiver is a man, not just a woman. For men, this applies primarily to retirement and beyond [1]. Additionally, as the average life expectancy has increased, the time spent caring for their parents has lengthened. Compounding this is the fact that they are often also entrusted with the care of their grandchildren to aid their children's economic endeavors, thereby leading to a dual caregiving burden [3].

The middle–old-aged group, which predominantly shoulders dual caregiving responsibilities, represents the baby boomer generation in Korea, that is, those born between 1955 and 1974. This demographic comprises approximately 17 million people, accounting for 32% of the country's total population [4]. As their aging parents become frailer over time and the demand for grandchild care increases, a growing number of individuals within this age group are expected to experience heightened caregiving stress and burden [1]. This life stage for the middle–old-aged group is also marked by emerging physical health challenges, potentially leading to decreased quality of life due to mental health concerns, such as depression and feelings of isolation [5]. Given that caregiving burdens directly influence caregivers’ well-being [6], measures to alleviate the dual caregiving strain are vital for sustaining the quality of life of the middle–old-aged group.

Although nursing research has addressed caregiving extensively, it has largely overlooked its dual complexities. The nursing profession is predominantly associated with direct and/or indirect patient care. Most existing studies target care providers, such as nurses and family members, attending to older adults with conditions such as cancer, chronic illnesses, and mental disorders [6-9]. Notwithstanding the growing societal recognition of the dual caregiving burdens experienced by middle-aged and older adults, the subject remains underrepresented in nursing research. In addition, studies dealing with dual caregiving burden are also focused on the balance of work and care for one generation through child or older parents' care [10]. Thus, there is a pressing need for studies that address the unique and diverse challenges faced by middle-aged adults who juggle the responsibilities of supporting multiple generations.

Therefore, this study aims to clearly identify and define the nature of the concept of dual caregiving burden for grandchildren and older parents of middle-aged and older adults according to Walker and Avant's conceptual analysis method [11]. By clarifying concepts, this study intends to understand the conceptual structure of dual caregiving burden in middle–old-aged and to redefine the value and meaning of caregiving. Additionally, we expect that this can be utilized as basic data for the development of policies related to nursing care services that can reduce the caregiving burden for middle–old-aged group.

METHODS

Ethical statement: Ethical statements: This study was exempted from approval by the Institutional Review Board as it is a review of the literature using previously published studies.

1. Research Design

This study was conducted following the concept analysis procedure of Walker and Avant [11] to establish a theoretical basis in nursing practice by clarifying the current usage of the concept and defining attributes of the dual caregiving burden by the middle–old-aged. The specific process involves selecting the concept (setting the purpose of concept analysis), identifying the uses of the concept (determining the attributes), model cases and additional cases (boundary cases, contrary cases, related cases), and antecedents and consequences of the concept, and defining empirical referents.

2. Data Collection

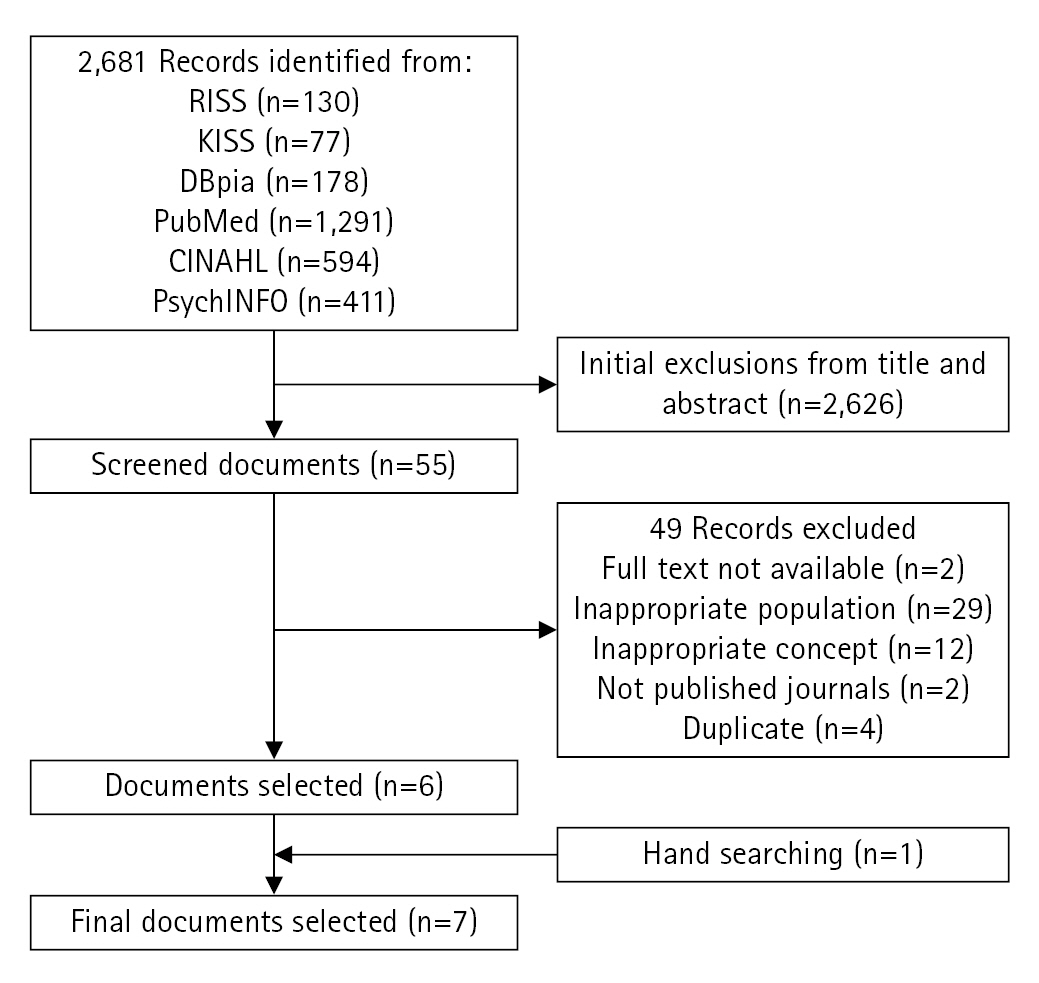

This study conducted a literature search for peer-reviewed articles published through March, 2023. To identify current usage and attributes of dual caregiving that distinguish it from a typical caregiving burden, we set search terms such as ((Double OR Dual) AND (Care OR Caregiv*)) OR (burden) using Boolean operators. There were a total of 130 articles from the Research Information Sharing Service, 77 from the Korean studies Information Service System, 178 from Nurimedia (DBpia), 1,291 from PubMed, 594 from CINAHL, and 411 from PsychInfo. The inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: (1) the paper should focus on people aged 50 and over, (2) the paper should be about the dual caregiving burden concept appearing in those who provide care for both parents and grandchildren, and (3) it should be written in either English or Korean. However, papers that mentioned dual caregiving burden but were only available as abstracts or included the concept only as a part of explaining other variables were excluded. An initial screening resulted in 55 papers, but some were excluded because the caregivers were not in the middle–old-aged, the care recipients were neither parents nor grandchildren, or the concept of dual caregiving burden was not revealed. Eventually, six papers were chosen, and one more was added through citation searching, resulting in a final count of seven (Figure 1, Appendix 1).

The researchers thoroughly read the final papers to define the concept and characteristics of the dual caregiving burden for parents and grandchildren in the middle–old-aged. The data, including attributes, antecedents, and consequences, were categorized and reviewed repeatedly. Using Walker and Avant's [11] analytical method, the present study delved into the lexicographical meaning, attributes, attribute verification, application examples, antecedents, and result variables of the concept of dual caregiving burden for parents and grandchildren among the middle–old-aged, along with the determination of empirical referents.

RESULTS

1. Literature Review on the Concept of Dual Caregiving Burden

1) Identifying the Uses of the Concept

To identify the definition of “dual caregiving burden” for the older parents and grandchildren of the middle–old-aged, we can decompose the term into its components. “Dual” is Korean for '[i-jung]', meaning a double layer that repeats or overlaps twice [12]. In English, it is expressed as “dual” or “double”, referring to having two different parts or an amount twice as much as usual [13]. “Caregiving” which is [buyang] in Korean, refers to activities that look after a person with no living ability [12] In English, “caregiving” signifies actions to maintain someone's health and safety [13]. “Burden” which is [bu-dam] in Korean, entails the assumption of some form of duty or responsibility [12]. It refers to a “burden” in English, signifying something challenging to accept, act upon, or handle [13]. Therefore, the lexicographical meaning of dual caregiving burden in Chinese characters, Korean, and English dictionaries can be defined as “the difficulty of accepting or handling the double duty performed to maintain a healthy life for someone without a living ability”.

2) Scope of Usage of the Dual Caregiving Burden Concept

(1) Usage of dual caregiving burden in other disciplines

In women's studies, Song [5] defined dual caregiving as “having to care for children under six and the older adults simultaneously.” The researcher argued that primary caregivers, especially women, had their everyday freedoms and mobility restrictions due to dual caregiving burdens. This has led to a structure in which women cannot participate in society. Notwithstanding the increased social services that have reduced the burden of direct and physical care, women still face increased levels of the burden from providing multiple levels of care, such as for their children, parents, and in-laws, while coordinating services for them, including waiting times. The time and energy they spend on these tasks has not decreased. Moreover, when the person requiring care is a male, the burden grows as everyday household chores also fall on the woman. Therefore, Song [5] emphasized the importance of men and women sharing the burden of care equally.

Hamilton and Suthersan [10] focused on the dual burden experienced by grandparents juggling work and childcare from the perspective of gerontology. Grandparents participate in caring for their grandchildren to foster relationships and allow their adult children to continue with their economic activities. However, they noted a trend in which grandparents' participation in economic activities decreased in order to assist their adult children's societal participation. Therefore, policies that balance paid work and unpaid care for their grandchildren are required to enable grandparents to work longer and have a more productive old age [10].

Women's studies have discussed the burden of dual caregiving. However, these discussions have primarily emphasized the importance of achieving gender equality in care provision due to the excessive burden this responsibility places on women. Gerontology defines the burden of dual caregiving as the strain grandparents experience while juggling their work with caring for grandchildren, rather than looking at it as the burden of caring for two different individuals. Discussions in this field have mainly revolved around the dual burden experienced in work and care. In other words, in other fields of study, the focus is less on the dual caregiving burden itself and more on maintaining the economic activities of women who are primarily responsible for providing care and other care providers.

(2) Concept usage in nursing

In the nursing field, it is difficult to find the literature that directly mentions the burden of dual caregiving. Instead, the concept of caregiving burden is examined. Certain terms, such as caregiving stress and caregiving strain, are used interchangeably with caregiving burden [6].

In nursing, there was the burden of care for patients with diseases such as cancer, dementia, and mental disorders [6,8,9,14,15]. In a study by Choi et al. [8] that investigated the burden of family care for older adults with cancer, the burden was high in the area of lifestyle changes as the caregivers' time and lives transitioned to be patient-centered. Previous research on patients with cancer by Nam [14] also reported that the caregiving burden was high for those with no other caregivers, longer caregiving time, existing illnesses, higher monthly medical expenses, and a significant decrease in income after cancer diagnosis.

Cho’s study [6] on the burden of family caregiving for patients with dementia at home underscores the importance of accurately understanding the burden of caregiving. The study suggests that this burden deteriorates not only the physical and mental health but also the quality of life of the families of patients with dementia. The study also anticipates an increase in the ages of spouses and adult children caring for patients with dementia, expecting this trend to lead to additional physical burdens for older family members of patients with dementia [6].

In nursing, studies on caregiving burdens often focus on families or family compositions centered on patients with health conditions rather than addressing caregiving burdens targeting two or more generations. Furthermore, these studies primarily examine individual reactions to the burden of caregivng rather than the care of the burden itself.

2. Provisional List and Defining Attributes of Dual Caregiving Burden

Based on the final selection of seven articles, the provisional attributes are listed as follows: first, the intergenerational redistribution of caregiving responsibilities focuses on multiple caregiving responsibilities for one individual in the middle-aged generation [A1,A2]; second, it is accompanied by physical and mental exhaustion [A1,A3]; third, it occurs when the individual from the middle generation, who might support older parents who cannot live independently and care for grandchild instead of their own children, has no alternative but to provide care [A1,A4]; fourth, care work and housework occur concurrently [A5]; and last, the compensation for caring for two generations is insufficient [A3,A6].

Based on the provisional list, the attributes of dual caregiving burden were selected and defined (Table 1). Dual caregiving burden entails “The overconcentration of caregiving onto the middle–old-aged generation, which persists when there are no alternatives for care provision outside the middle–old-aged caregiver. This burden also blurs the distinction between care work and housework, and the compensation for these roles is insufficient.” Therefore, the attributes of the dual caregiving burden for older parents and grandchildren in the middle–old-aged group identified in this study are given as follows: ① the overconcentration of caregiving in the middle–old-aged; ② the absence of alternatives for caregiving outside the middle-aged generation; ③ ambiguity in the scope of caregiving roles; and ④ insufficient compensation for caregiving for two generations.

3. Model Case

A model case should include all the attributes of the dual caregiving burden for the older parents and grandchildren of the middle–old-aged and does not have to include the attributes of other concepts. The following model case demonstrates the concept [11].

Mr. Kim, 66 years old and retired last year, lives with his 88-year-old father who has been diagnosed with chronic kidney failure. His younger brothers are yet to retire, so he cares for his father. His father needs to visit the hospital regularly for dialysis, and since he is frail and has difficulty moving due to old age, he accompanies him on his visits ①. He also has a 3-year-old granddaughter. His daughter has returned to work after finishing her maternity leave; therefore, he visits his daughter's house daily to care for his granddaughter. His daughter and son-in-law are often too busy working overtime to care for the child; therefore, he raises his granddaughter ①. Although caring for his father and granddaughter alone is difficult, he cannot quit because he knows that his family's financial situation is insufficient to afford a nursing home for his father or hire a babysitter for his granddaughter ②. He provides care without compensation ④, but his family considers his caregiving something that should be done naturally ④.

There would have been fixed working hours when he had been in an office job, but caring for his father and granddaughter does not have such a schedule. When his daughter and son-in-law come home late from work, he often takes the young granddaughter to his home, spending countless days caring for both his father and granddaughter ③. His father has never done housework and has difficulty moving around, so all the housework falls on him. In addition, because his daughter and son-in-law cannot manage household chores due to their busy work lives, Mr. Kim has to help around the house. Considering his daughter's efforts to maintain her job in difficult circumstances, he does all the housework at his daughter’s house ③. In this way, Mr. Kim works tirelessly until bedtime, both in his and his daughter's house.

4. Additional Cases

1) Borderline Case

A borderline case includes only some of the important attributes of the concept; therefore, it cannot be considered as the concept [11].

Park is a 67-year-old woman who recently retired honorably from her job as an elementary school teacher. She decided to retire because she was tired of her 30-year career as a teacher, and because her 30-year-old daughter had given birth, she wanted to help raise her grandson. Her daughter is on maternity leave, but the baby is still not sleeping throughout the night, so she does not get enough sleep. Park 'goes to work' at her daughter's house at 10 a.m. every morning, and she takes care of her grandson while her daughter catches up on sleep. While her daughter is sleeping, Park helps with housework and looks after her grandson. When her daughter wakes up at approximately 1 p.m., they eat lunch together, and Park returns home ①.

Her 79-year-old father-in-law was diagnosed with stomach cancer during a health checkup. He underwent surgery, but lymphatic metastasis was detected, and the doctor recommended eight chemotherapy sessions at three-week intervals. Consequently, they moved to the same apartment complex to receive Park's assistance. Park began accompanying her in-laws to the hospital because it was difficult for the two older adults to visit the outpatient clinic alone ①. Park, who helps her daughter in the morning, cares for her in-laws in the afternoon without any compensation and comes home late in the evening ③, was suggested by her husband to place her father-in-law in a nursing home and not visit her daughter's house often. However, Park expressed her desire to express gratitude to her in-laws for their help during her younger years, which allowed her to balance parenting and work by helping them. She also wanted to help her daughter because she received help from her mother when she gave birth to her first child and had difficulty sleeping.

2) Contrary Case

A contrary case is a clear example of what the concept is not and contains none of the important attributes of the concept [11].

Mrs. Kim, the 59-year-old woman, is a doctor who lives with her husband and 85-year-old father with diabetes. She maintained an independent life while caring for her father. If her father’s care was required during work hours, she left it to her husband or used professional care services, allowing her to focus on daily life and work. Mrs. Kim, who lives with her father, receives financial compensation for his care from siblings who do not live with their father. She managed her health appropriately and received regular checkups at the hospital once a year. As a doctor, she had no difficulty maintaining her health, preventing diseases, or receiving appropriate treatment. Mrs. Kim shared house chores with her family (husband). She invests time and energy in leisure activities. Her daughter and sons-in-law were actively involved in raising their daughters. When Mrs. Kim and her husband go on monthly trips, their daughter, son-in-law, care for granddaughter and her father. In addition, when the daughter and son-in-law go on trips, Mrs. Kim and her husband care for their granddaughter.

5. Identifying Antecedents and Consequences

Antecedents are events or occurrences that must occur before the concept, while consequences are events or occurrences that result from the concept. Thus, determining the antecedents and consequences of a concept can further clarify its attributes [16].

The antecedents of the dual caregiving burden of the middle–old-aged group for older parents and grandchildren are presented (Table 1): (1) social context (dual-income, aging) [A1]; (2) individual’s tendency toward caregiving responsibility [A2]; (3) social expectations of caregiving roles [A6]; and (4) lack of support system [A7]. The consequences of dual caregiving burden are stated as follows (Table 1): (1) physical and mental exhaustion [A1,A3]; (2) self-care deprivation [A3]; and (3) restrictions on social activities [A6].

6. Empirical Referents

The final step in the concept analysis of the dual caregiving burden for older parents and grandchildren in the middle–old-aged, the empirical referents herein, involves the identification of experiential targets for significant attributes in the real world [11]. These empirical references can be found in the instruments that have been developed. However, no instrument was developed for dual caregiving among the middle–old-aged caring for older parents and grandchildren.

However, a similar concept, dual care responsibilities [17] measures whether a person is providing care for two generations and whether they are responsible for sharing care and household chores. These instruments included information about the type of dual caregiving, one of the attributes of the dual caregiving burden analyzed in this study. The family caregiver burden instrument [18] included the same attributes of caregiving burden as those analyzed in this study, including being forced to provide care and having conflicts with other family members about providing care.

In addition, empirical references to dual caregiving burden can be found in news articles dealing with real-life issues. In South Korea, those in their 50s and 60s are responsible for caring for everyone, from their parents to their grandchildren, and rather than receiving compensation for care, they are experiencing an increase in care-related expenses [15,19]. In the case of caregiving, they also have to do housework, and if they do not provide care, there are substantial expenses related to the hiring of caregivers and babysitters. They provide care to reduce such expenses [20,21].

According to the study, dual caregiving burden is the overconcentration of care burdens on the middle–old aged, which persists in the absence of care alternatives other than caregivers, the blurring of roles with no distinction between caregiving and housework, and the lack of recognition of their value.

DISCUSSION

According to the results of this study, “dual caregiving burden” is defined as a concept in which the caregiving workload is concentrated on the middle-aged generation and continues in situations where there are no alternatives for caregivers. The scope of work is ambiguous, with an unclear distinction between caregiving and housework, and its value is not fully recognized. The antecedents identified include social contexts, such as dual income, low birth rate, aging society, an individual's strong sense of caregiving responsibility, societal role expectations, and inadequate support systems. Social conditions such as dual income, low birth rate, and aging increase the burden of dual caregiving; the stronger the individual's caregiving responsibility and societal role expectations for caregiving and the less social support there is, the greater the dual caregiving becomes. In addition, physical and mental exhaustion, self-care deficiency, and social activity limitations were identified as outcome factors. However, there have also been reports of positive outcomes in which the dual burdens of caring for older parents and grandchildren offset each other when there is adequate support [21]. Thus, the dual caregiving burden causes caregivers to experience negative outcomes that are reduced depending on the presence or absence of a support system. Therefore, there is a need to establish a social support system that can increase family bonds and reduce the burden of dual caregiving. In particular, domestic caregiving policies approach child and older adults care individually and fragmentarily, focusing on caregiving recipients, resulting in insufficient support for caregivers [22]. Therefore, the paradigm should be changed to a caregiver-centered policy to alleviate the burden on dual caregivers.

In South Korea, those providing dual care are primarily “baby boomers” in their 50s and 60s, accounting for 14.5% of the total population [4]. Therefore, the negative outcomes resulting from their dual caregiving burden have significant implications for a substantial proportion of the population. South Korea's care policies tend to be distinctively divided, with childcare policies directed toward early education and older adult-related care policies, such as the long-term care insurance system, implemented based on aging-related diseases in older adults [22]. Middle-aged and older women who are caregivers often fall into a welfare blind spot, highlighting the need for welfare policies focusing on not only for care recipients but also for caregivers.

Previous studies have suggested that the burden of caregiving significantly affects the relationship between caregivers and care recipients [22]. Based on the results of this research and previous studies, there is a need to introduce counseling programs that allow for reflection on the relationship between the caregiver and the care recipient in situations where the caregiving burden converges on the middle-aged generation and there are no alternative care providers. Caregivers, who bear the burden of dual caregiving, should actively utilize counseling to understand their interactions with care recipients and objectively reflect on and accept their dual caregiving situations. This helps prevent the degradation of care quality and abuse resulting from the neglect or avoidance of care recipients’ needs.

This study identified physical and mental exhaustion, as well as self-care deficiencies, as the resulting factors. As the health of caregivers is linked to the quality of care experienced by the care recipients [23-25], the development of solutions for relieving caregiver fatigue and self-care deficiency is necessary. Hence, programs that allow caregivers to continuously receive healthcare, such as linkage programs at public health centers, are deemed necessary. Moreover, as dual caregivers experience tension and fatigue comparable to dual labor workers, the institutionalization of rest services is required [26]. Based on previous research, it is necessary to devise ways to secure rest time for caregivers within the community, such as by providing support for alternative human resources.

The significance of this study lies in its provision of insights into the increasing reality of middle–old-aged providing dual caregiving for their older parents and grandchildren, and the need for proactive solutions to the burden of dual caregiving. Based on the attributes of the caregiving burden converging on the middle generation, the lack of alternative caregivers, and the ambiguity of the scope of work and its unrecognized value, it is evident that specific social support and policies are needed. A detailed understanding of dual caregiving, not for older parents and children but for the middle–old-aged generation's older parents and grandchildren provides direction for systematic support measures for dual caregiving. This study also offers a direction and vision for establishing counseling and health linkage programs for the middle–old-aged providing dual caregiving. Building upon this foundation, it further provides a basis for developing customized community support programs, as well as education and training programs specifically tailored for the middle–old-aged providing dual caregiving. Furthermore, it lays the groundwork for including the aspect of dual caregiving in physical, mental, and emotional preventive health care strategies, thereby indicating significant implications for nursing practice and research.

Therefore, based on the aforementioned results, future studies should be conducted from more detailed and diverse perspectives to develop tools, counseling, and linkage programs related to the dual caregiving for older parents and grandchildren by middle-aged and older individuals. By applying these tools and programs, it will be possible to validate the results and reduce the burden of dual caregiving.

CONCLUSION

This study performed a concept analysis in line with Walker and Avant's [11] eight-step concept analysis to understand the attributes of the dual caregiving burden for older parents and grandchildren among the middle–old-aged generations and derive empirical referents accordingly.

The attributes of the dual caregiving burden for older parents and grandchildren among the middle-aged and older generations identified in this study are as stated follows: (1) the overconcentration of caregiving in the middle–old-aged generation; (2) the absence of alternatives for caregiving outside of the middle generation; (3) ambiguity in the scope of caregiving roles; and (4) insufficient compensation for caregiving for two generations. The antecedents include societal circumstances (e.g., dual-income families, low birth rate, aging population, etc.), an individual's strong caregiving responsibility, societal role expectations regarding caregiving roles, and a lack of support systems. As a result of these antecedents, physical and psychological exhaustion, neglect of self-care, and limitations in connection to social activities have emerged as consequence factors.

This study broadens the understanding of dual caregiving burden experienced by middle–old-aged caring for older parents and grandchildren. While this study has included mental exhaustion as a consequence of dual caregiving burden, it may not have thoroughly explored the depth and multifaceted nature of emotional strain experienced by caregivers. This could be a limitation in terms of fully understanding the intricate dynamics of dual caregiving burden. Nonetheless, this study offers an initial understanding of the dual caregiving burden among the middle–old-aged caring for older parents and grandchildren and makes a significant contribution to geriatric nursing research and policy development in this field. Future research should delve deeper into the emotional and psychological aspects of the dual caregiving burden.

Based on the attributes and empirical referents in this concept analysis study, tools can be developed to measure dual caregiving burden. Therefore, nursing interventions can be devised to alleviate this burden. Subsequent research can apply these tools and interventions to verify their effectiveness. This would significantly contribute to the pool of knowledge concerning the nursing of the middle-aged and older generations.